Harry S. Truman Book Award | March 16, 2016

2016 Harry S. Truman Book Award

Winner Announced, Read an Excerpt

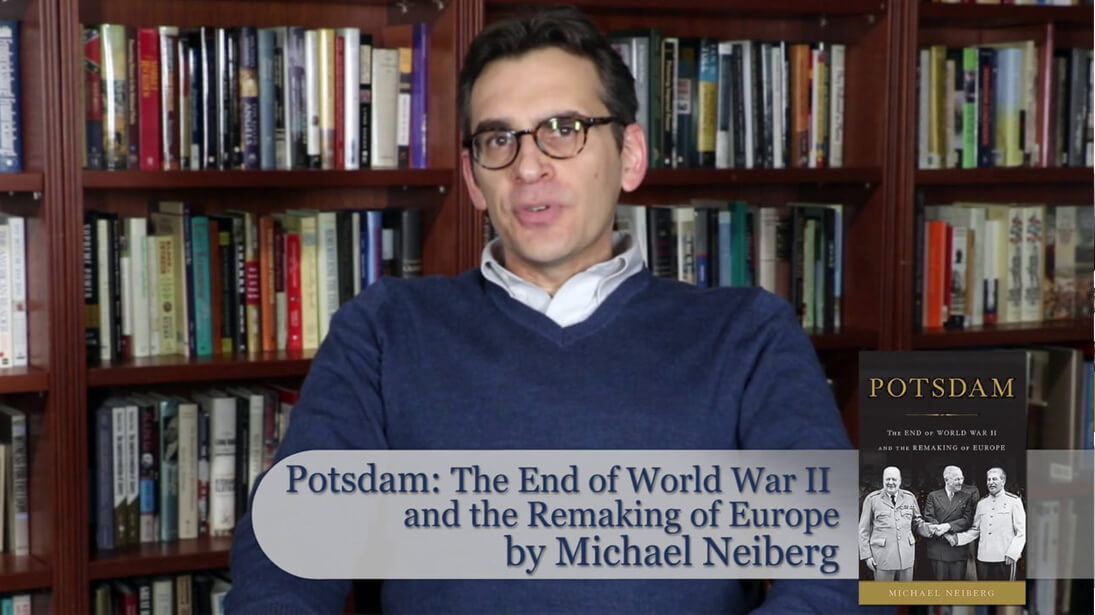

Potsdam: The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe (Basic Books/Perseus Books Group, 2015) by Michael Neiberg is the winner of the 2016 Harry S. Truman Book Award.

The Harry S. Truman Book Award is presented biennially by the Truman Library Institute. Established in 1963, the Harry S. Truman Book Award recognizes the best book published within a two-year period dealing primarily and substantially with some aspect of the history of the United States between April 12, 1945 and January 20, 1953, or with the life or career of Harry S. Truman.

Michael Neiberg is a professor of history and the Stimson Chair of the Department of National Security and Strategy at the U.S. Army War College, and the author of several award-winning books.

Dr. Neiberg’s book was selected from a field of 25 entries, which included such other important books such as Doomed to Succeed: The U.S.-Israel Relationship from Truman to Obama by Dennis Ross and Genesis by John B. Judis.

Reviews

Geoffrey Wawro, author of A Mad Catastrophe: The Outbreak of World War I and the Collapse of the Habsburg Empire

“Michael Neiberg has given us a taut, masterful account of Potsdam, revealing that the Big Three operated more from fear—of each other, of their peoples, of their rivals, and of fast-moving events on the ground—than from any degree of confidence or certainty. The Cold War was born at Potsdam, and Neiberg seats us at the conference table, to feel the tension and acrimony.”

Wall Street Journal

“An easily digestible page-turner.”

Financial Times

“[A] crisp, elegantly organized account of Potsdam…. [An] excellent book.”

Potsdam

The End of World War II and the Remaking of Europe

By Michael Neiberg

Excerpt from the Introduction

Copyrighted Material

On June 28, 1919, the same day that much of the rest of the world marked the signing of the Treaty of Versailles that officially ended the Great War, a US Army captain strolled down the aisle of his local church to marry his sweetheart. Although he had distinguished himself in the war and proven himself as a leader in the battlefield, he had little desire to make the military a career. Nor did he, at this point in his life, express any special desire to enter the world of politics. He and another veteran of the war had instead taken out a lease in order to open a men’s clothing store. The war had ended. In the future, he hoped, he would spend his time thinking about his family and his business, not war. On this day of all days his thoughts were far from wars and the peace treaties that end them.

Across the Atlantic Ocean on that same day, a controversial British politician was savoring a second chance. Having been humiliated and forced from office a few years before, he now had a dominant voice in Britain’s defense policies as secretary of state for war and air. Anxious about the postwar world and fearful of the growth of Soviet-style Bolshevism, he had advocated an Allied operation to land British, American, and Japanese soldiers in northern Russia in support of the pro-czarist “Whites” in the Russian Civil War. He disliked the Treaty of Versailles, calling it “absurd and monstrous,” in large part because he thought it weakened Germany too much. A dismantled Germany, he feared, could leave a deadly power vacuum in Europe that the Bolsheviks might seek to fill. Wanting to see Bolshevism “strangled in its cradle,” he saw the Versailles Treaty as a missed opportunity to remake the postwar world. As early as 1920 he had begun to call for major revisions to the treaty in Germany’s favor because of the “unreasonable demands” it made on the Germans, the only possible counterweight on the European continent to the potentially even more dangerous Russians. When the time came for him to write a postwar treaty, he would argue for rejecting the Treaty of Versailles as a model.

The Bolsheviks then fighting the Bloody Russian Civil War took little notice of the Treaty of Versailles. Their revolutionary ardor already anathema to the British, French, and Americans, the Bolsheviks had sealed their diplomatic isolation by surrendering to the Germans in the Treaty of Best-Litovsk in March 1918. That surrender had given the Germans the resources they needed to launch the spring offensives in France that nearly won them the war that year. After the German surrender, therefore, the war’s victors had seen no reason to invite the Bolshevik regime to the peace talks in Paris. To Bolshevik leaders, including the newly named People’s Commissar for Nationalities, the issues surrounding the Treaty of Versailles paled in comparison to the life-or-death struggle they were waging against the czarist Whites. Only the treaty’s formation of a new Polish state directly affected them. The ambitious commissar, however, took careful note of the attempts of the Western Allies to support the Whites; he had especially noted the menacing “strangle in its cradle” phrase one of the Western leaders had used. Years later, and under radically different circumstances that a new war had created, he would have the opportunity to meet the man who made that statement and tell him in no uncertain terms his opinion of it.

Two of those three men – British Secretary of State for War and Air Winston Churchill and the Soviet Union’s commissar for nationalities, Joseph Stalin – may well have foreseen themselves leading their nations in war and peace. Both men recognized the fragility of the new peace negotiated in Paris and had divined that Europe’s period of peace would likely not last long. Ambitious men close to the centers of power in their respective countries, Churchill and Stalin knew that no treaty in and of itself could resolve the core issues of the murderous period of global conflict that had begun in that disastrous summer of 1914. The idea that in the next war they would fight shoulder to shoulder as allies likely would have struck them both as ludicrous in 1919, although they had seen enough radical change in their lifetimes that perhaps nothing would have surprised them too much.

VIEW UPCOMING EVENTS.

GET FREE ADMISSION AT AMERICA’S PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARIES.

SEE WHAT’S ON EXHIBIT AT THE HARRY S. TRUMAN LIBRARY AND MUSEUM.