The Unwritten Record | June 25, 2024

No Mail, Low Morale: The 6888th Central Postal Battalion

“No mail, low morale,” or so the motto goes. Even before the founding of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion, the mail was piling up for the soldiers serving during World War II. The ever changing locations, duty stations, and movements caused a logistical challenge for getting the mail delivered on time.

The Women’s Army Corps (WAC) was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and set to active duty status on July 1, 1943. Further, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, a civil rights leader, advocated for the inclusion of African American women in the WAC. It would take an even further push to send them overseas to serve supporting the war effort.

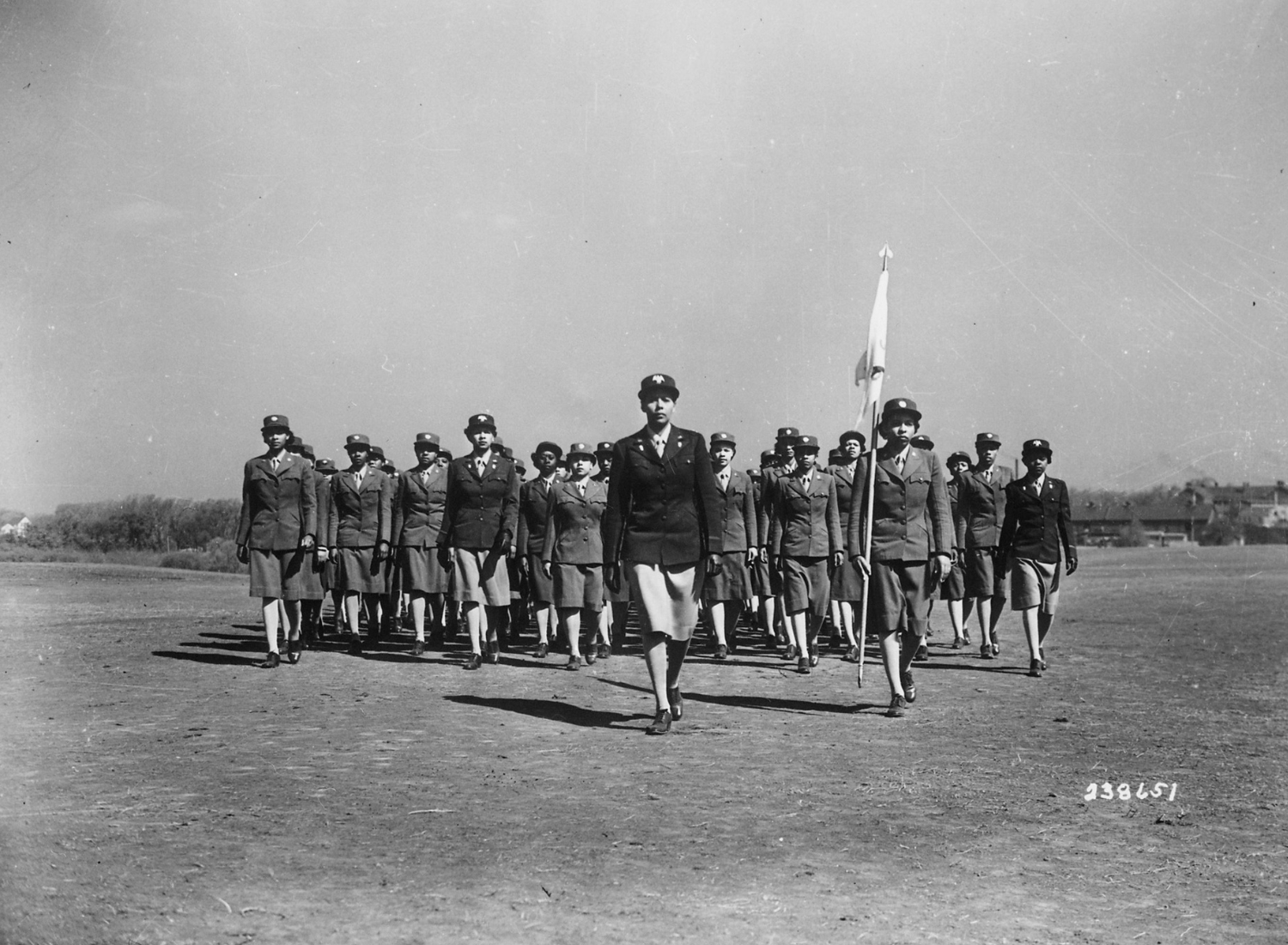

The 6888th Central Postal Battalion, also nicknamed the “Six Triple Eight,” were not only the sole all African American battalion in the WAC, but they also were the only all African American, all women battalion sent overseas during World War II. Major Charity Edna Adams commanded the battalion and over 800 volunteers joined the 6888th Central Postal Battalion throughout the war. The unit was self-sufficient and included medics, administrative personnel, dining hall workers, and more.

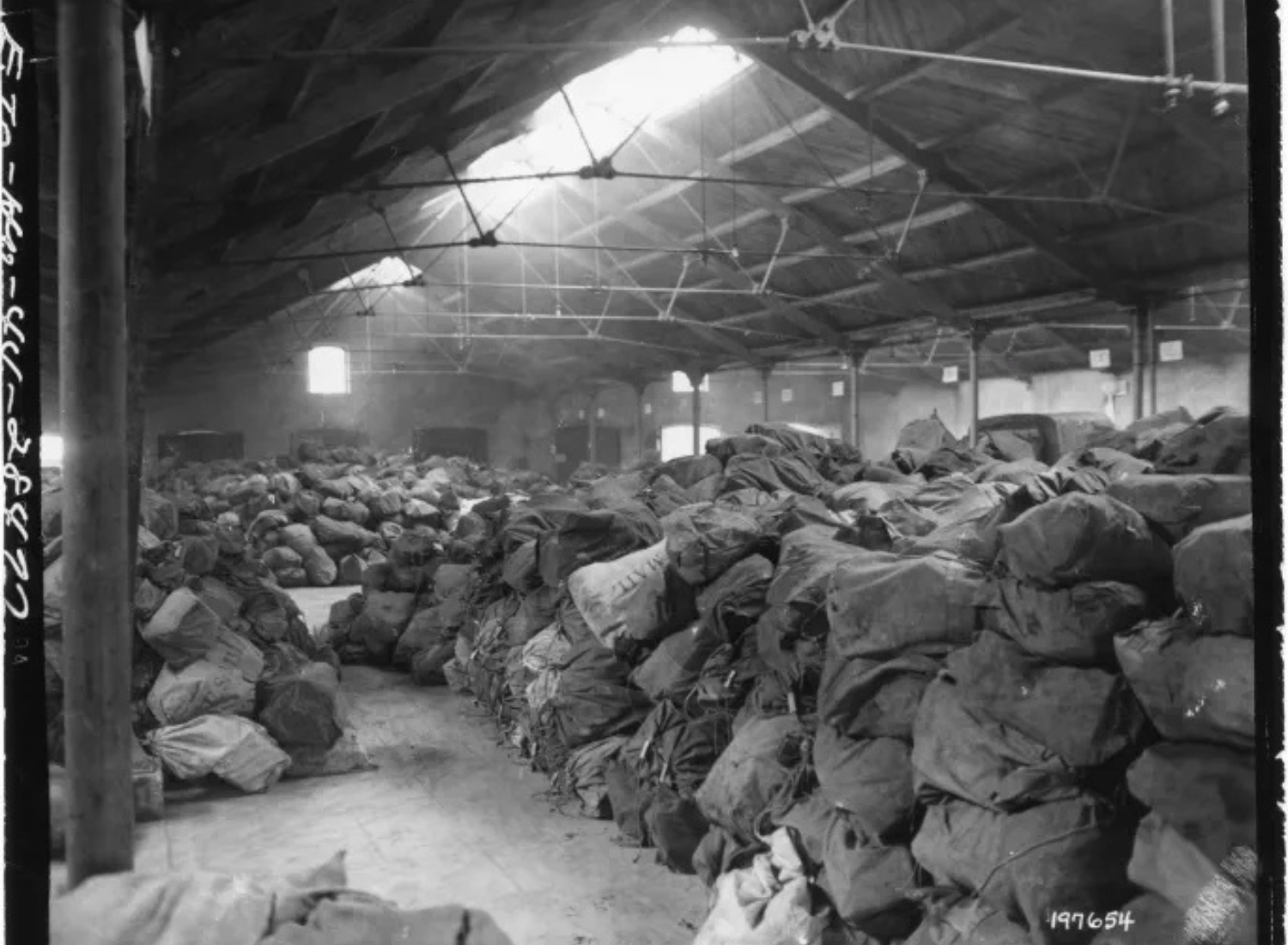

After their training in Fort Oglethrope, Georgia, and the trip across the Atlantic in the ship Ile de France, the Six Triple Eight arrived in Birmingham, England via train. The overflowing warehouses were stacked with letters and packages for anxiously awaiting soldiers. Three separate eight-hour shifts, seven days a week would ensure they worked around the clock to deliver the mail. Their motto, “no mail, low morale” would guide them.

Original Caption: “Somewhere in England, Maj. Charity E. Adams,…and Capt. Abbie N. Campbell,…inspect the first contingent of Negro members of the Women’s Army Corps assigned to overseas service.” Local Identifier: 111-SC-200791; National Archives Identifier: 531249.

Their task was not easy. Any “undeliverable” mail was routed into their hands. They diligently tracked servicemembers with their seven million information cards to determine who and where each piece of mail should go to.

During their time in Birmingham, they enjoyed dancing, bowling, and local restaurants. They were also invited by locals for tea and Sunday dinner. Soon, however, they had processed the full backlog of mail and were on their way to France on June 9, 1945, a month after V-E day. They participated in a victory parade in Rouen, France, where they passed the spot where Joan of Arc was executed.

The backlog in Rouen also proved daunting, however, the Six Triple Eight took on the task alongside French civilians and German POWs. Some undelivered mail dated back two to three years, and took roughly five months to completely sort. Similarly to Birmingham, the women enjoyed various sports in their off-time, including tennis, basketball, and even ping pong.

Original Caption: “One of the two similar buildings, in France, which house the vast quantities of Christmas mail en route to American soldiers.” The 6888th would sort similar piles. Local Identifier: 111-SC-197654.

At the end of World War II, the Six Triple Eight’s numbers were severely reduced by roughly 300 personnel as they continued working through additional undelivered mail in Paris. Then, in February 1946 the 6888th Central Postal Battalion returned to the United States and was disbanded at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

The legacy of the 6888th Central Postal Battalion continues today. On February 25, 2009, a public event at the Women in Military Service for America Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery honored the work of the 6888th, and on November 30, 2018 a monument in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas was made in their honor. Most recently in April 2021, the US Senate passed legislation to award the 6888th Central Postal Battalion with the Congressional Gold Medal, and the bill will now go to the House of Representatives.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Of the 855 women of the 6888th, only 6 were alive to receive the Congressional Gold Medal in 2022. Today, only two of the women survive.

Written by Sarah Bseiraini, this post originally appeared on February 8, 2022 on The Unwritten Record, a blog published by the National Archives.

You might also like:

Remembering the Resolute Ms. Romay Catherine “Johnny” Johnson Davis and The Six-Triple Eight

Truman Civil Rights Symposium, Washington, D.C. July 2023

Legacy Letter: Truman and Civil Rights

Join our email list to receive TRU History, event alerts and Truman Presidential Museum updates: