Exclusive Book Excerpt | March 11, 2022

Exclusive excerpt from Jeffrey Frank’s newest book

The Trials of Harry S. Truman – sheds light on 75th anniversary of the Truman Doctrine

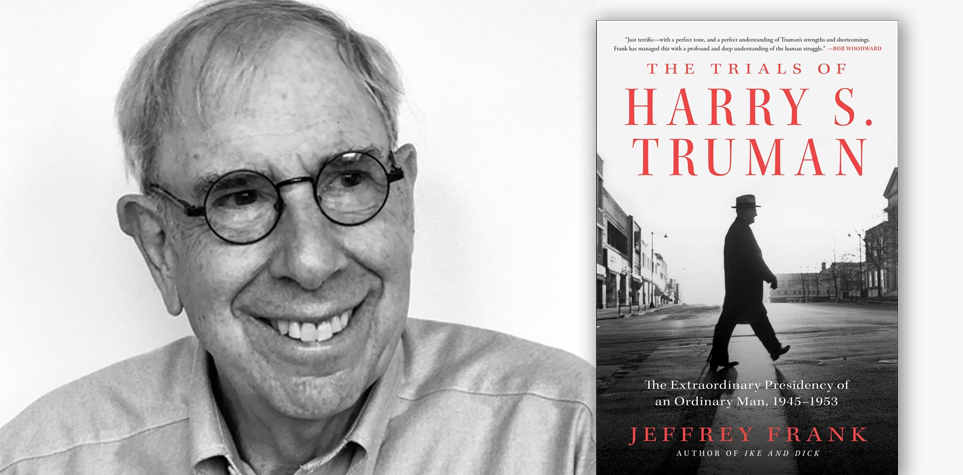

Jeffrey Frank, author of the bestselling Ike and Dick, returns with the first full account of the Truman presidency in nearly thirty years, recounting how so ordinary a man met the extraordinary challenge of leading America through the pivotal years of the mid-20th century.

The nearly eight years of Harry Truman’s presidency—among the most turbulent in American history—were marked by victory in the wars against Germany and Japan; the first use of an atomic weapon; the beginning of the Cold War; creation of the NATO alliance; the founding of the United Nations; the Marshall Plan to rebuild the wreckage of postwar Europe; the Red Scare; and the fateful decision to commit troops to fight in Korea.

Historians have tended to portray Truman as stolid and decisive, with a homespun manner, but the man who emerges in The Trials of Harry S. Truman is complex and surprising.

The Trials of Harry S. Truman was released on March 8, 2022 and is available wherever books are sold.

“Dawn of the Doctrine”

By Jeffrey Frank, excerpted by the author from The Trials of Harry S. Truman: The Extraordinary Presidency of an Ordinary Man, 1945-1953

BY 1947 IT WAS COMMONPLACE to view the nations of the postwar world as potential chess pieces, or dominos, although the “domino theory” wouldn’t enter the political phrasebook until the Eisenhower era. The influential columnist Walter Lippmann, looking at the growing enmity between the United States and the Soviet Union, warned that Russia wanted to “take the Balkans, Turkey, Iran, Iraq—the whole region—out of the British sphere of influence and to absorb it into the Soviet sphere.”

Britain’s “sphere of influence” then was near the vanishing point, and in February, 1947, Lord Halifax, the British ambassador, informed Secretary of State George C. Marshall that Great Britain intended to cut off military support to Greece and Turkey. Marshall saw that as “tantamount to British abdication from the Middle East.” With no other country able to act as an economic guarantor, a consensus quickly built that, in the words of a State Department speechwriter, had “handed the job of world leadership, with all its burdens and all its glory, to the United States.”

Six days after Halifax’s message, Marshall and Dean Acheson, the Under Secretary of State, walked across 17th Street to the White House, to meet with President Truman and congressional leaders, to make the case for sending American aid—as much as four hundred million dollars. Truman spoke first, but it was Acheson who poured it on: Soviet pressure, he said, was felt in the Urals, Iran, and northern Greece, which could mean opening “three continents to Soviet penetration.” He compared these potential targets to “apples in a barrel infected by one rotten one,” and said “the corruption of Greece would infect Iran, would also carry infection to Africa through Asia Minor and Egypt, and to Europe through Italy and France, already threatened by the strongest domestic Communist parties in Western Europe.” He went on to say that they faced “a situation which has not been paralleled since ancient history…. Not since Athens and Sparta, not since Rome and Carthage have we had such a polarization of power.”

In Acheson’s recollection, a long silence followed this extravagant historical parallel. Then Senator Arthur Vandenberg, a Michigan Republican who’d become chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee after the 1946 midterms — a Democratic rout — turned to Truman and said, “Mr. President, if you will say that to the Congress and the country, I will support you and I believe that most of its members will do the same.” There was a story, often repeated, that, as he was leaving, Vandenberg added, “The only way you are ever going to get this is to make a speech and scare hell out of the country.”

Truman was unlikely to question what was being urged by Acheson and Marshall. Their outlook suited him, and supported his view of America’s role in the post-1945 world. His memoirs contain a number of passages in which he recalled acting with resolve, prepared to show the willingness of a muscular nation to defend a weak one. All this was prelude to what became known as the Truman Doctrine, a template for action—the idea, as Truman would soon put it, that “wherever aggression direct or indirect, threatened the peace, the security of the United States was involved.”

In the matter of Greece and Turkey, Truman believed that he needed to appeal directly to Congress, and he did so, on March 12, 1947, in a speech delivered to a joint session and a nationwide radio audience. It had been almost two years since President Roosevelt’s death, but Americans were still unaccustomed to Truman, and a voice variously described as “flat,” or “Midwestern,” or “nasal,” or “clipped.” Nor were they yet accustomed to an assertive foreign policy encapsulated by what became the speech’s most quoted passage: that “it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or outside pressures. I believe that we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way.”

Truman later recalled making last-minute changes, replacing the word “should” with “must” in those two sentences, because “I wanted no hedging in this speech… It had to be clear and free of hesitation or double talk.” He was describing the actions of the resolute leader that he wanted to be.

Parts of the speech got a standing ovation, but the applause was far from universal. Although Acheson told congressional skeptics that the United States didn’t intend to send troops– that there was no intention to assist just any nation that asked for help– the Ohio senator and presidential aspirant Robert Taft wasn’t persuaded. He called Truman’s speech “a complete departure from previous American policy,” and saw the loans to Greece and Turkey as signaling acceptance of the principle “of dividing the world into zones of political influence, Communist and non-Communist.” He warned that the nation had “accepted the philosophy of force as the controlling factor in international relations.” Others wondered why the United States should pick up after the British. World leadership had a nice ring, but apart from the glory of it all, there were practical drawbacks—strategic and economic. It would have sounded heartless to say such a thing, but shoring up a fragile nation could be much like adopting a family that no one truly cared about.

Acheson, quoting the State Department speechwriter Joseph Jones, would later write that everyone in Truman’s circle was “aware that a major turning point in American history was taking place.” It was certainly a turning point in Truman’s reputation. The idea that “he’s not big enough for the job” was being supplanted by a view that he seemed “destined to have a very definite niche in history,” as the Washington Post’s Edward Folliard wrote, adding that “in generations to come, American schoolchildren will be required to bone up on the Truman Doctrine, the epochal policy he laid before Congress.” Unconvinced, the Wall Street Journal’s Vermont Royster, in a column published the next day, wrote that Truman had “asked the United States to embark on a long road from which there is no turning,” and that he had taken the words of the Monroe Doctrine, from 1823, and “applied them to the world”—a policy bound to have consequences that Royster did not need to spell out.

There was not yet talk of a “Cold War,” although that phrase, already appropriated by Lippmann in columns and a book, quickly made its way into the language. But Truman’s nineteen-minute speech was nonetheless an announcement that this chilly conflict was already being fought. As Joseph Jones later wrote, “The convergence of massive historical trends upon that moment was so real as to be almost tangible.” This historical convergence certainly affected, and transformed, Harry Truman, who found himself in the inescapable role of leading an American colossus, the world’s only superpower, with ambitions to change the world.

Critical Acclaim for The Trials of Harry S. Truman

“Just terrific—with a perfect tone, and a perfect understanding of Truman’s strengths and shortcomings. Frank has managed this with emphases on sociology, culture, and a profound and deep understanding of the human struggle.” – Bob Woodward

“A remarkable window into America’s great Cold War president. Because Frank is such a sublime writer, his heroic recounting of the Truman presidency is dazzling. This is intellectual biography at its absolute finest.” — Douglas Brinkley is the Katherine Tsanoff Brown Chair in Humanities and Professor of History at Rice University and author of American Moonshot: John F. Kennedy and the Great Space Race

“Massively researched, engagingly written… An intimate, revealing history of a time, and of a president, whose straightforward persona masked a more complicated, sometimes tortured man during a truly extraordinary period.” — Robert L. Messer, author of The End of an Alliance: James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt, Truman and the Origins of the Cold War

“An intimate, vivid portrait of our 33rd president and his times…. a chance to rediscover one of the most improbable and compelling figures in American history.” — Rick Atkinson, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of The Liberation Trilogy and The British Are Coming.

MORE TO EXPLORE

4/28/2022 Wild About Harry – featuring Jeffrey Frank and CIA Director William J. Burns

Plan Your Visit to the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum