The Funeral of Harry S. Truman | December 26, 2022

Truman’s Funeral

By Brian Burnes

On the afternoon of Thursday, December 28, 1972, Bess Truman – hatless, wearing a black coat and using a cane – walked out of her home at 219 North Delaware in Independence, Missouri through its back door and entered a waiting limousine.

There were five limousines in all. The first carried Mrs. Truman and their daughter, Margaret. Other cars held Margaret’s husband, Clifton Daniel, their fours sons, and members of the Truman household staff. Their destination was the Truman Library in Independence, the site of the main memorial service for Harry Truman, who had died two days before.

Operation Missouri

The ceremony was the principal maneuver of Operation Missouri – what the U.S. Army called the former president’s funeral. The plans had been in existence since the early 1960s, and the 600-page document called for thousands of soldiers to play various roles, with events stretching over several days. The funeral procession was supposed to include nine black horses, a caisson to bear the casket, a horse holder for the traditional military riderless horse, other horse caretakers, and a veterinarian.

But much of that never appeared in Independence.

Though the former president Truman had signed off on the original plan, he also had asked that his family’s wishes be considered, and ultimately a far less elaborate service occurred. This was largely out of respect for Mrs. Truman. Then in her late eighties, she was fatigued after the 22-day ordeal that her last husband had endured before finally passing away. But several observers also noted that the simplified funeral was much in keeping with the former president, who often disdained pomp, especially when it concerned himself.

In the early 1960s Truman had been contacted by officers with the U.S. Fifth Army, stationed at Fort Same Houston in Texas, to discuss plans for the funeral. Early in the discussions Truman had announced that he didn’t want his body to be taken to Washington to lay in state in the Capitol rotunda. Neither did he want to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

“I would like to be buried out there,” he said one day at his Truman Museum office, pointing out the window to the museum courtyard. “I want to be out there so I can get up and walk into my office if I want to.”

At the end of the planning process, Truman reviewed a slide show detailing the planned funeral service. According to one account, the presentation had ended with an uncomfortable silence, which Truman broke.

The plans looked fine, he said, adding, “I sure wish I could see it myself.”

Hometown Memorial

After Truman’s death, a motorcade was substituted for the elaborate procession, and various heads of governments did not attend. Instead, the federal government scheduled a separate memorial service in Washington on January 5.

But even in its abbreviated form, the Truman funeral in Independence involved 3,000 soldiers. Of those, about 300 members of Battery D of the Missouri national guard reported right away. Their first responsibility was to stand guard during the repose period of Tuesday and Wednesday outside the Carson Chapel funeral home in Independence.

After Truman died on Tuesday morning, December 26, at Kansas City’s Research Hospital and Medial Center, his body was taken to the Carson funeral home. Mrs. Truman had viewed her husband’s body for the last time there, a few hours after his death. Then the light brown mahogany casket had been sealed.

Early on Wednesday afternoon, eight military pallbearers carried the former president’s casket from the funeral home to a hearse, their path flanked by 44 soldiers. The hearse then traveled the 15 blocks from the funeral home to the Truman Museum. Along the route, 856 members of the U.S. armed forces stood, each separated by ten steps and each saluting as the hearse passed. The motorcade eased by the Truman home, where all but one of the window shades had been drawn. From that window, Mrs. Truman watched the procession pass.

When the hearse arrived at the Truman Museum’s south portico at 1:15 p.m., 21 Air Force jets roared overhead. That afternoon, President Richard Nixon and former president Lyndon Johnson flew into separate airports and paid visits to the Truman Museum within minutes of one another.

But Operation Missouri was not long on limousines. Far more numerous were the buses of the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority, which operated free shuttles from the parking lot of the Harry S. Truman Sports Complex to the Truman Museum, often running a bus every three minutes.

Mr. Truman’s body lay in state in the front lobby of the Truman Museum from 3 p.m. Wednesday, then until 11:26 a.m. on Thursday.

Paying Last Respects

Thousands of Kansas City area residents waited for an average of two hours to file past a closed casket draped with an American flag bearing 48 stars, the number of states in the Union when President Truman occupied the White House. But the visitors did not so much want to view the former president’s casket as to show their respect. The line stretched from the museum doorway, down the driveway, and out to U.S. 24. “Everyone walked quickly through the east door, around the casket and out the west door,” a Kansas City Star reporter noted. By 4:15 a.m., more than 26,000 people had filed through. [Note: CBS Evening News would later put the total at 75,000.]

Later, early on Thursday afternoon, Mrs. Truman rode the limousine to a back entrance to the Truman Library. The crowds that had waited in line were gone by the time the funeral guests began to arrive, showing their invitations to members of the military honor guard.

Among those present in approximately 250 seats in the small auditorium of the Truman Museum were W. Averell Harriman, former ambassador to the Soviet Union; John Snyder, former treasury secretary; and Clark Clifford, former special counsel to Truman.

Final Salute

But there also was Robert E. Sanders, the Independence resident who had painted the Truman home; George Miller, Harry Truman’s barber; Thomas Hart Benton, the artist who had rendered the mural in the Truman Museum’s front lobby; William Story, a library guard; Vietta Garr, the Truman family’s longtime cook and assistant; Rose Conway, Truman’s personal secretary; Mike Westwood, the Independence police officer who served as Truman’s bodyguard and companion for nearly twenty years; and about 30 members of Battery D, Truman’s World War I artillery unit. The guest list, as printed in The Kansas City Times, included friends like Independence lawyer Rufus Burrus and onetime Independence postmaster Edgar Hinde, who dated their friendships with the former president back to the 1920s.

One reporter noted the juxtaposition of Truman’s generation with a later one. “As the cars drove up to the entrance of the library, a few young persons in miniskirts or maxi-length hair were escorted in by the military,” she wrote. “But the greater number were older men and women, some with canes. There goes Averell Harriman and Clark Clifford…Mrs. Eddie Jacobson, widow of Truman’s partner in his early haberdasher days.”

The service started at 2 p.m. and lasted just over 30 minutes. Mr. Truman’s casket rested on the stage of the auditorium. The Reverend John Lembcke, rector of Trinity Episcopal Church, where Harry and Bess Truman had been married in 1919, read from the Twenty-seventh Psalm. W. Hugh McLaughlin, grand master of the Missouri Masonic community, read a short statement. There were no long eulogies, reflecting the belief of the former president that a person’s life should speak for itself.

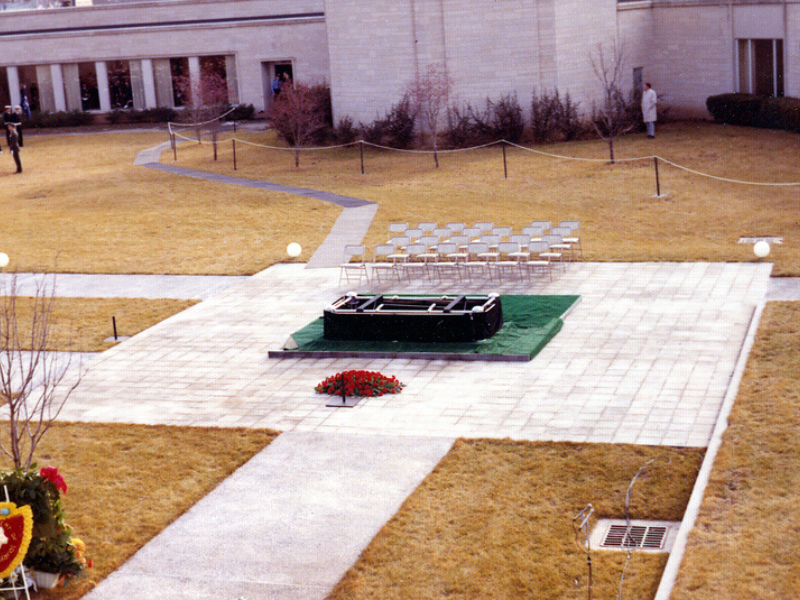

The ceremony then moved to the Library’s outdoor courtyard. After all visitors and officials were in place, the family, led by Mrs. Truman – now being seen in public for the first time since her husband’s death – walked to the chairs provided them.

“Man, that is born of a woman, hath but a short time to live, and is full of misery,” said the Reverend Lembcke, beginning the committal service. “He cometh up, and is cut down, like a flower…”

Mrs. Truman accepted the folded flat from her husband’s casket. The service ended with a 21 gun salute from the six 105mm howitzers of Battery D of the Missouri National Guard, positioned on the library’s front yard.

This article is excerpted with permission from Harry S. Truman: His Life and Times by Brian Burnes.

Read “Truman’s Death” by Brian Burnes.

All images featured in this post are part of the extensive online photography collection of the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum.