TO SECURE THESE RIGHTS

By Steven F. Lawson, Professor Emeritus, Rutgers University

PART III: POSTWAR VIOLENCE

When the war ended in August 1945, the biggest threat to the racial status quo came from black veterans returning home expecting to find a new day for democracy. Similarly, mothers and sisters of black veterans were proud of the achievements of their husbands, fathers, and sons. In Columbia, Tennessee, thirty-seven-year-old Gladys Stephenson, a domestic worker whose eldest son James served in the Navy, exhibited the self-respect that World War II fostered. In late February 1946, she stood up to a clerk in a radio repair shop who refused to fix a radio that she wanted her son James to have after returning from the military. Her unwillingness to follow the code of southern etiquette and defer to a white man set in motion a chain of events that precipitated a race riot in her town.15

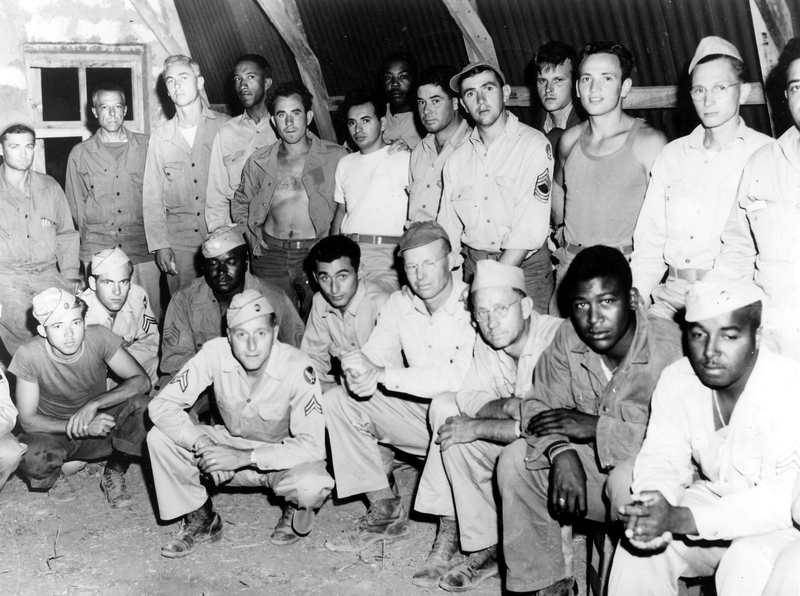

Stressing the need for interracial solidarity in the post-war world, Black and white soldiers united for this photo at a heavy bomber base in Italy, March 1, 1945. Courtesy Truman Library, photo 72-3952

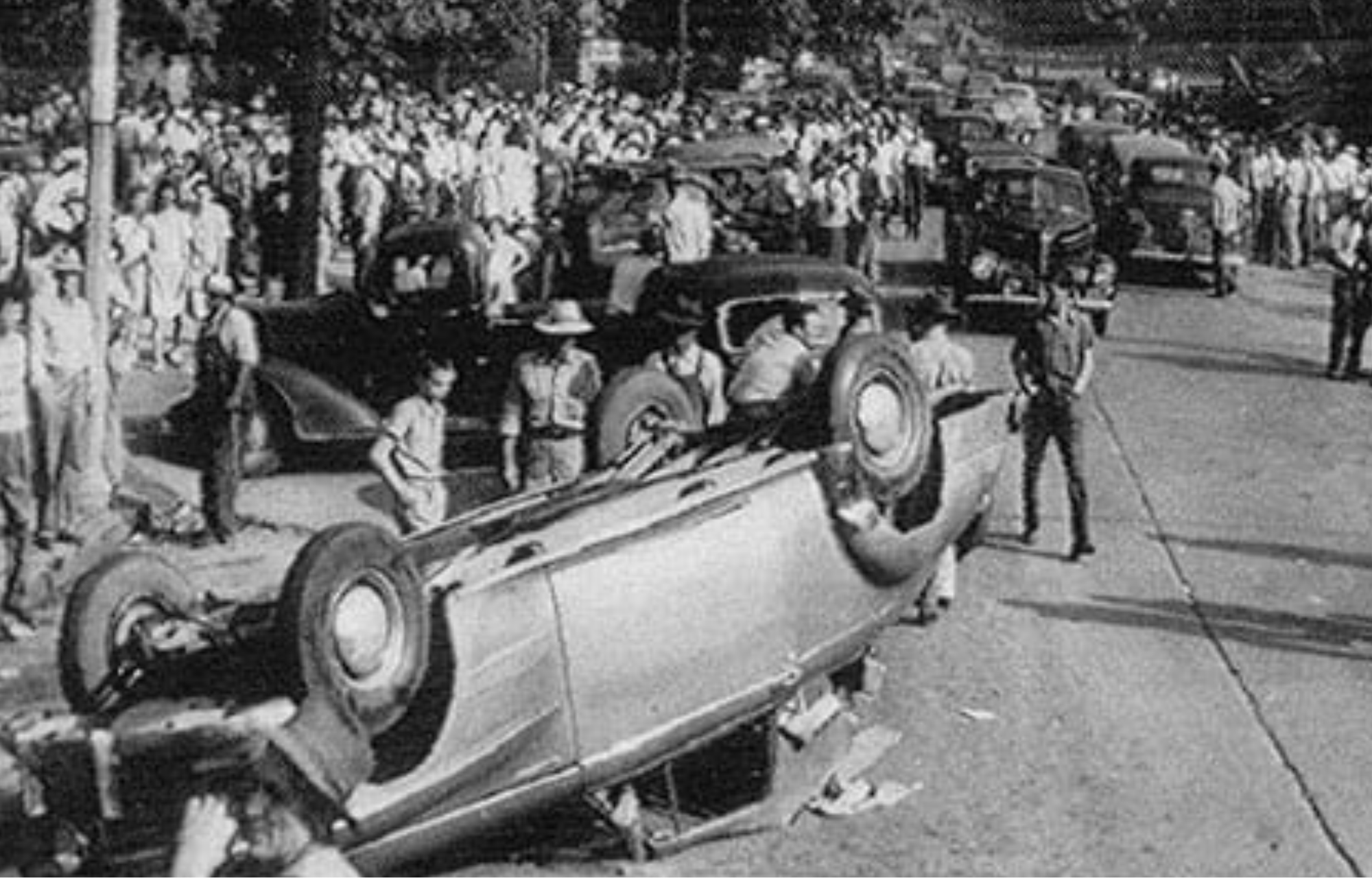

The white clerk, Billy Fleming, also a veteran, did not take kindly to Gladys Stephenson’s complaint that the repair shop had not treated her fairly. Before she and her son could exit the building, Fleming attacked James Stephenson from behind, and the two began to slug it out, crashing through windows and tumbling into the street. Gladys Stephenson then picked up a shard of glass and delivered a glancing blow to Fleming’s shoulder. Several bystanders managed to break up the brawl, and the police arrived shortly to arrest the Stephensons, but not Fleming, for attempted murder. Rumors about the incident quickly circulated through Columbia and surrounding Maury County, the site of two lynchings over the previous twenty years. The sheriff, who had a good relationship with local blacks, released the Stephensons into the custody of African American civic leaders for their own protection. They returned to the black section of town called the “Bottom,” where armed residents stood guard against white marauders coming to retrieve the mother and son.

On the evening of February 25, amidst a great deal of confusion, city police officers moved into the area, precipitating an exchange of gunfire that wounded four officers. With the situation spiraling out of control, the sheriff called upon the state governor to send in reinforcements. Rather than restoring calm, the Highway Patrol roared into the Bottom and shot up and ransacked black business establishments and social clubs, beating up and wounding several residents. In the early morning hours of February 26, the Patrol, joined by members of the Tennessee State Guard, finally brought a halt to the hostilities. They took 100 blacks into custody, confiscated their weapons, and incarcerated them in the local jail. Two of those held were shot and killed by the police while under questioning, accounting for the two fatalities that occurred during the “Columbia riot.” Eventually, twenty-eight black Columbians were indicted on attempted murder charges; ironically, the Stephensons, whose actions (along with Fleming’s) had ignited the fracas, never stood trial.16

Tennessee race riots, 1946. Courtesy Tennessee State Library and Archives

The Columbia incident, among others, demonstrated that although the war had brought African Americans some notable gains, the United States had a long way to go before it truly became the land of liberty and justice for all. Proof of this was unfortunately abundant. On February 13, two weeks before the Columbia clash, a black veteran named Isaac Woodard, still in his military uniform, was riding a Greyhound bus from Camp Gordon, Georgia, to his apartment in New York City’s East Bronx. In Batesburg, South Carolina, Woodard got off the bus to clean himself up in the segregated washroom and took more time than the driver thought reasonable. The Greyhound operator called the police to arrest Woodard for disturbing the peace. The officers did not like Woodard’s attitude; they beat him severely and poked him in the eyes with a nightstick, leaving the former soldier blind.

Five months later, two other atrocities occurred. In Monroe, Georgia, on July 25, 1946, a black veteran, Roger Malcolm, his wife, and his sister-in-law and her husband, were gunned down and killed by the Ku Klux Klan. Malcolm had just been released from jail for stabbing his white employer, who had tried to flirt with Malcolm’s wife. Not only did Malcolm not remain submissive, but he represented to the Klan “bad Negro” veterans who returned from the war and were “getting out of their place.” On August 8, still another black ex-G.I, John C. Jones, and his cousin, Albert Harris, were released from jail in Minden, Louisiana, after having been arrested for loitering. That day a group of whites in cahoots with a deputy sheriff attacked the pair and blowtorched Jones to death, though Harris managed to survive the beating and escaped.17

PREVIOUS: Part II – The Impact of World War II

NEXT: Part IV – Pressure for Reform

Navigate through this essay by section: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Notes