Benevolent Diplomacy: Children’s Art and U.S. Food Relief in Occupied Germany | December 15, 2017

Welcome guest blogger Kaete O’Connell, a Ph.D. candidate in history at Temple University, who received a Research Grant to explore the archives at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum thanks to the generosity of Truman Library Institute members and donors. Thank you to the American Historical Association for allowing us to reprint her blog post on food relief in post-war Germany.

Last winter while leafing through the official file at the Truman Library for material on Herbert Hoover’s 1947 economic mission to Germany, I was struck by a vibrant burst of color. The monochrome of telegrams and correspondence was replaced by colorful sketches of chickens, Lifesaver candies, and a family of beans marching to a can for preservation. The drawings were bound together with thank-you notes penned by young recipients of U.S. food relief. German children clearly appreciated the “gift” of food, pleasing occupation officials keen to capitalize on American charity. German stomachs, particularly young ones, offered an alternate route to hearts and minds in the early Cold War. At a time when the future of foreign assistance programs remains uncertain and military rhetoric is ascendant, we might look back to the experience in postwar Germany, when the United States practiced altruism as a form of diplomacy. For a brief moment, before Cuba, before Korea, and even before Berlin, the United States cultivated an image that relied as much on beneficence as military might.

Last winter while leafing through the official file at the Truman Library for material on Herbert Hoover’s 1947 economic mission to Germany, I was struck by a vibrant burst of color. The monochrome of telegrams and correspondence was replaced by colorful sketches of chickens, Lifesaver candies, and a family of beans marching to a can for preservation. The drawings were bound together with thank-you notes penned by young recipients of U.S. food relief. German children clearly appreciated the “gift” of food, pleasing occupation officials keen to capitalize on American charity. German stomachs, particularly young ones, offered an alternate route to hearts and minds in the early Cold War. At a time when the future of foreign assistance programs remains uncertain and military rhetoric is ascendant, we might look back to the experience in postwar Germany, when the United States practiced altruism as a form of diplomacy. For a brief moment, before Cuba, before Korea, and even before Berlin, the United States cultivated an image that relied as much on beneficence as military might.

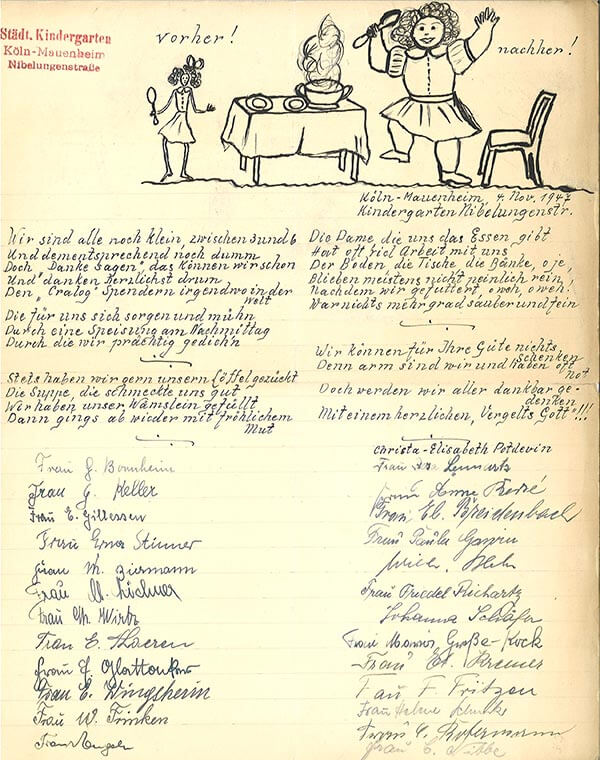

A sketch and a poem created by German children sent to the American Friends Service Committee. Courtesy of the American Friends Service Committee Archives, fair use

Feeding defeated Germany accomplished multiple objectives for the United States: it provided proper nutrition for a hungry populace, increased American prestige, and offered soft power resistance in the early struggle against communism. While the success of German food relief appears a forgone conclusion, it almost failed to materialize. Americans overwhelmingly supported relief programs for liberated populations, but this did not extend to German civilians. Relief work in Germany was confined to displaced persons camps, in line with the assumption that a punitive occupation was the best insurance against future conflict. However, recognizing hunger as an obstacle to peace, President Truman revised the policy, authorizing food imports and permitting voluntary agencies such as CARE and CRALOG to operate within German borders in 1946.

The food situation in Germany worsened before it improved, but the focus on the youngest members of German society swayed public support in favor of continued humanitarian aid, with Americans forgoing a “hard peace” in favor of a narrative that underscored the United States as a benevolent power. Military officials calculated the success of food relief strictly in numbers, but the human response to U.S. food and feeding offers an alternative measure. Letters and artwork created by German children provide a lens to uncover the impact and legacy of American food relief.

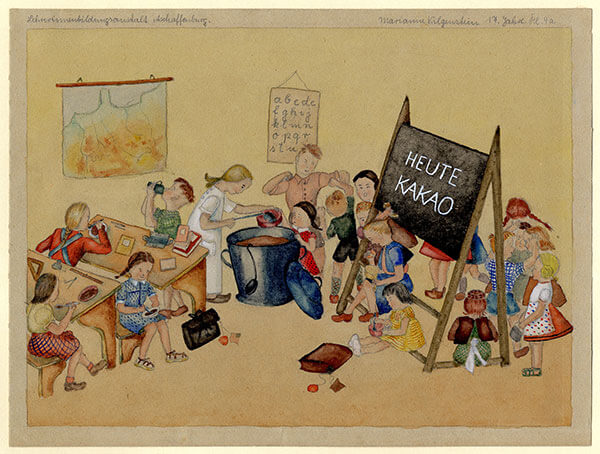

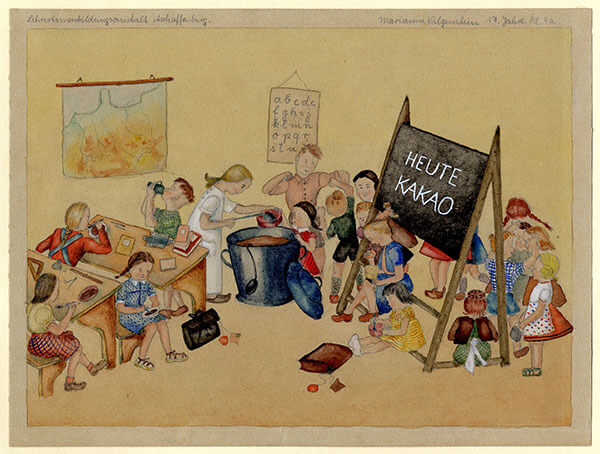

Image 2: A drawing by Bavarian schoolchildren emphasizes their favorite food, cocoa. Courtesy of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, fair use

The thank-you note is arguably a lost art form, but in the 1940s it was status quo, even in postwar Germany. The letters showcase a wide array of creative media and modes from the generic (those children whom I imagine were merely doing as told by their parents or teachers) to the didactic (careful diaries of food received and the children’s knowledge of its origins) to the impressively imaginative (poetry was not uncommon). Occasional notes of dismay regarding weekly rather than daily hot cocoa appear, but most of the letters are laudatory, a chorus of praise—“Schmeckt gut!” (Tastes good!) Some pieces were composed by teachers and signed by the class, but overwhelmingly these letters were written by individual children, with several demonstrating mastery of the English language.

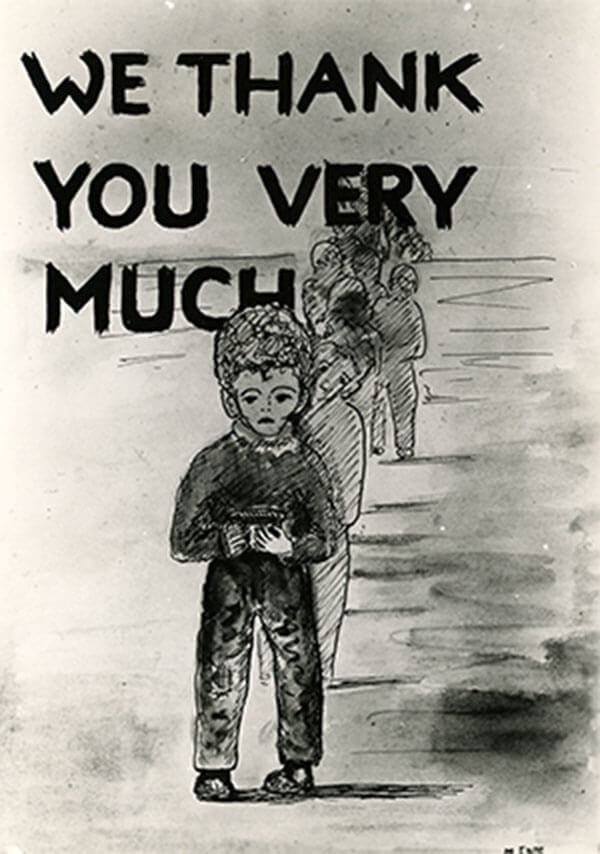

Image 3: An illustration by German schoolchildren shows a line of presumably hungry kids. Courtesy of the Tracy S. Voorhees papers, Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries, fair use

The drawings include crude stick figures, but also impressive works of art created by German teenagers. Humor is apparent in many. The sketch in Image 1 (sent to the American Friends Service Committee alongside a poem) appears inspired by the German folk story “Die Geschichte vom Suppen-Kaspar” in Der Struwwelpeter, a dismal story about a young boy who refuses to eat his soup and starves to death. In postwar Germany, the reverse occurs, thanks in part to U.S. aid. Image 2 was included in a portfolio presented to President Truman by Bavarian schoolchildren. The drawing emphasizes a favorite food among the children, Kakao (cocoa), so prized that it provoked a fistfight. While many of these illustrations are lighthearted, German children were not immune to the gravity of their situation. One drawing gifted to military government officials stands out with its depiction of a gaunt child at the fore of an endless line of presumably hungry kids, eliciting haunting memories of the war’s aftermath two years on (Image 3).

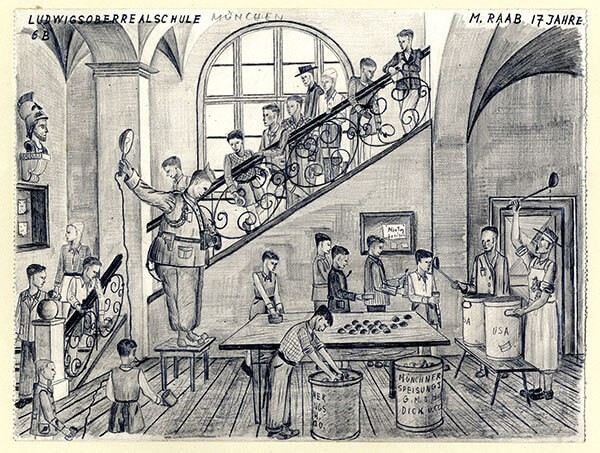

There is only so much one can read into this art, both the literal representations and the motives behind its creation. How many thank-you notes did I begrudgingly write to distant relatives in my youth? While it remains difficult to measure gratitude, the drawings do confirm its existence. It was important to American officials that Germans appreciated this charity. Artwork like this confirmed to them that German youth both appreciated the gift of food and knew of its origins. But, I would argue, German youth were also aware of the propaganda value of the school feedings at this critical moment in the early Cold War. Image 4, which was included in the portfolio gifted to Truman, depicts a queue of thin German boys receiving food from pots marked USA while a portly military official attempts to snap a photo.

Image 4: German boys line up to receive food from pots marked USA, while a military official snaps a photo. Courtesy of the Harry S. Truman Presidential Library and Museum, fair use

The American occupation of Germany is often credited with providing the foundation for an improved U.S.-German relationship that reverberated throughout the trans-Atlantic community. Navigating the rubble of postwar Europe, the United States assumed a leadership role in relief and recovery, investing in the future rather than retreating inward. In Germany that meant providing schoolchildren with soup and cocoa, forging a bond that was not soon forgotten. Occupation officials and humanitarians couched their arguments for food relief in concern for future generations, relying on rhetoric and imagery that united nutritional concerns with democratic intentions. The political circumstances of the emerging Cold War contributed to the growing acceptance of food and feeding as diplomatic tools, used to reward anti-Communists while reinforcing the image of America as a land of plenty. Food aid for Germany was not without its critics. The goodwill it garnered, however, confirmed to officials the diplomatic merits of humanitarian aid, projecting an image of American benevolence that remains significant today.

Thank you Kaete, for this enlightening glance into post-war Germany!

This post originally appeared on the American Historical Association blog.

Join our email list to receive more Truman updates right in your inbox: