Captain Truman: From Soldier to President | March 21, 2018

Harry S. Truman may have entered World War I as a struggling farmer, but he left with the leadership skills and a personal network of friends that launched him into a lifetime of public service that culminated with him becoming one of the greatest presidents of the United States. Rising through the ranks from first lieutenant to captain, Truman built on his personal integrity and strong work ethic to develop his leadership style, earn the respect of his troops and inspire them.

As a boy Truman dreamed of attending West Point and becoming a career Army officer, but although he passed the written test, he failed the eye exam and was denied entry. Undeterred from the desire to serve, Harry took matters into his own hands in 1905, memorized the eye chart and joined the National Guard.

War Hits

Twelve years later when President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war in April 1917, there were many reasons Truman did not have to serve. He was too old for the Selective Service Act at 33 years old, he had completed his service in the National Guard six years prior, he had poor eye sight and he was already part of the war effort as a farmer. Nevertheless, he reenlisted in the National Guard.

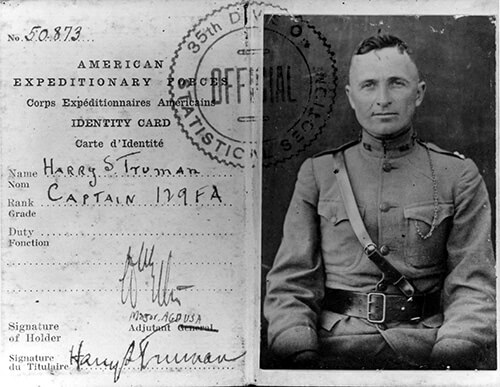

As was common at that time, Truman was banded together with local men to enlist and serve together, and these same men elected him to serve as one of their officers. On July 11, 1918, Truman was put in command of Battery D of the 129th Field Artillery, 35th Division. The regiment was comprised mostly of men from the Kansas City area, including Jim Pendergast who served in Battery B and was the nephew of Thomas Pendergast, who later helped launch Truman’s political career.

Battery D was wild, undisciplined and proud of this reputation. They were a cohesive and athletic bunch, fiercely loyal to each other. Mostly Irish and German Catholic boys, many of them were students and graduates of what was then called Rockhurst Academy.

Truman’s first day in command of Battery D was a challenging one. Truman later recalled, “I’ve been very badly frightened several times in my life and the morning of July 11, 1918, when I took over that battery, was one of those times.”

On that first day he faced 200 hungover and rowdy young men, many of whom were already detained to quarters for drunk and disorderly behavior. They were not initially impressed with their new captain. Sgt. Edward McKim remembered that Truman’s “knees were knocking together,” and Pvt. Floyd Ricketts thought Truman “gave the impression of a professor more than he did an artillery officer.” That night the men staged a drunken brawl in an effort to fluster their new captain.

Truman was not so easily spooked, though. He quickly established discipline and order in the group in such a way that earned his men’s respect, and very soon after they saw him as an effective leader. Truman demoted the existing officers and in their place promoted Sgt. William F. Tierney and Cpl. Eugene P. Donnelly.

The Western Front

Once Battery D was stationed in France, their respect for Truman only grew. “I don’t think he’d ever been under fire before either and it didn’t bother him a damned bit,” later recalled Pvt. Vere Leigh. Truman told his fiancee Bess a different story, however, “My greatest satisfaction is that my legs didn’t succeed in carrying me away, although they were very anxious to do it.”

Above all, Truman worked to do what he believed was right and protect his troops — even if it meant disobeying orders — and Truman did not lose a single man to combat.

In September 1918, Battery D marched through grueling rain to the Argonne Forest for what was the largest action in American military history at that point — the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Truman’s superior, regimental commander Col. Karl Klemm, started demonstrating unusual behavior. He rode up and down the line shouting orders “like a crazy man,” Truman remembered, including senselessly ordering an advance at double-time up a long hill.

Truman challenged Klemm’s orders. Through trickery and at times direct confrontation, the future president defended his fatigued solders from the erratic orders and bizarre behavior of their senior officer. When asked what he was doing allowing men to rest, Truman simply responded, “Carrying out orders, sir.” He failed to mention that the orders he was carrying out were his own.

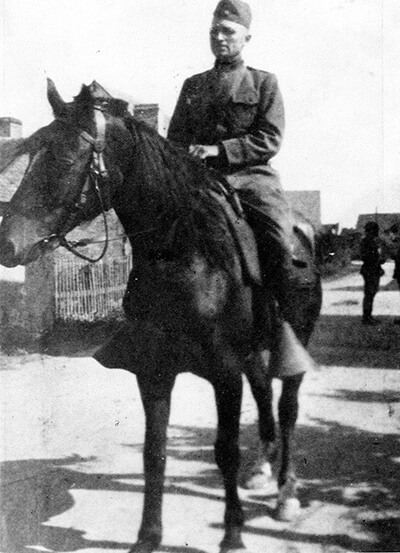

Truman opposed Klemm again when one of his soldiers twisted an ankle. Truman

allowed Sgt. Jim Doherty to ride on his horse, which was meant to be only for officers.

When Klemm saw an enlisted man on Truman’s horse, he flew into a rage on the sight and ordered Doherty down. Truman responded that as long as he was in command of the battery, Doherty would ride. Doherty stayed on Truman’s horse.

Truman later wrote in his diary, “The Colonel insults me shamefully. No gentleman would say what he said. Damn him.”

Leading at All Costs

Perhaps Truman’s most notorious defiance of orders was when he ordered his men to fire out of sector. In World War I, batteries were under strict orders not to fire on targets beyond a narrow assigned sector in front of them because of the well-founded fear that they could accidentally kill American soldiers in neighboring units. While in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, however, Truman observed German cannons out of sector on his left flank setting up to fire on the infantrymen that Battery D was supporting.

Truman took it on himself to disobey the order of not firing out of sector and called on his men to destroy the enemy guns.

Klemm severely reprimanded Truman for his disobedience, yet when facing the same situation the next day, Truman knew what he had to do. He had his men destroy a dangerous German battery located outside of Battery D’s sector yet again.

Truman’s disobedience of his command was enough reason for him to be court martialed if not for the timely intervention of Gen. John J. Pershing, who recognized Truman’s quick decision-making as a proper display of initiative that saved the lives of many American soldiers.

Through all of this, Truman’s troops knew their captain was risking his career to defend them, and they became even more devoted to him.

When discussing this incident at the Truman Library many decades later, former Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates said, “Truman understood that in a democratic society, common decency builds a respect. It’s a respect that prompts people to give their all for a leader.”

Homeward Bound

When Battery D was headed home after the Allied victory, they took up a collection from proceeds of a craps game on board the ship home and purchased a loving cup to present to Captain Truman. It was inscribed, “Presented by the Members of Battery D in appreciation of his justice, ability and leadership.”

Truman’s influence as the leader of Battery D was undoubted, even decades later. In fact, 79 of the 138 surviving members of the battery marched with Truman in his 1949 presidential inaugural parade. On that day — as he did nearly every day — he wore his bronze World War I Victory pin proudly on his lapel. Eight years later, on July 6, 1957, members of Battery D and their spouses joined former President Truman at the dedication of the Truman Library in Independence.

As Truman assumed the presidency and led the nation through the next world war, he was guided by his own experiences as a soldier in the First World War, even saying “My whole political career is based on my war service and war associates.”

This story originally appeared in the Special WWI Issue of TRU Magazine, a magazine delivered free to Truman Library Institute members.

The captivating story of Truman’s service in World War I is on display this year only at the Harry S. Truman Library and Museum in the special exhibition, ‘Heroes or Corpses’: Captain Trumain in World War I. Plan your visit today to view this temporary exhibition, included in museum admission or free for members.

Join our email list to receive Truman updates right in your inbox: