President Harry S. Truman and his Secretary of State Dean Acheson may have come from vastly different backgrounds, but the two developed a lifelong friendship based on their deep patriotism and affinity for politics that continued well beyond their years in the White House. Diplomat Karl Inderfurth has explored this relationship in his new play, “Harry and Dean,” which the Truman Library Institute is honored to premiere and post in its entirety in honor of the 75th anniversary of Truman’s presidency.

SCENES

Stage Announcements – by Clifton Truman Daniel

Prologue Union Station 1946

Scene 1 Inauguration Day 1953

Scene 2 “That’s his job”

Scene 3 Dropping the Bomb

Scene 4 Recognizing Israel

Scene 5 Firing MacArthur

Scene 6 Yale Chubb Fellow

Scene 7 “Captain with the mighty heart”

Epilogue Union Station 1953

Bio Sketch of Karl Inderfurth

STAGE ANNOUNCEMENTS (by Clifton Truman Daniel)

Music in background from Chopin’s Opus 42 Waltz in A Flat.

Music goes quiet. Lights in theater dim. Stage dark.

Ladies and Gentlemen, I am Clifton Truman Daniel, the eldest grandson of President Harry Truman, and I would like to welcome you to this performance of ‘Harry and Dean.’

As you get comfortable, we ask that you take this time to switch off any electronic devices you may have brought with you. For those who may feel a bit disoriented in this unconnected state, we shall only inconvenience you for about 90 minutes.

Regarding the play itself, it owes its inspiration to the book “Affection and Trust: The Personal Correspondence of Harry S. Truman and Dean Acheson from 1953 to 1971”. David McCullough has said there’s been nothing like that correspondence in our history, except for the post-presidential exchange between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. This play is faithful throughout to the Truman and Acheson letters, their memoirs, and the history of their years in office.

At the same time — as Dean Acheson’s son David put it in his delightful account “Acheson Country” — “My father always believed a good story does not have to be an affidavit, that is, the juice of entertainment should not be squeezed out by fanatical literary accuracy”. A wise admonition!

One more pre-curtain announcement. The music being played as you entered the theater was my Grandpa’s favorite – Chopin’s Opus 42, known as the ‘Two-Four’ Waltz. Our 33rd president once aspired to be a concert pianist, but his political aspirations – and fate – intruded!

Music briefly resumes, then fades. Play begins.

PROLOGUE UNION STATION 1946

Steam whistle and sounds of train approaching station.

Curtain rises. On the screen Union Station 1946 appears, followed by b & w film footage of train pulling to a stop, steam released. It’s a bleak, misty day. Platform virtually deserted.

Footage freezes and spotlight appears on Acheson standing off to one side of the platform. Another spotlight on a solitary Truman, with a book under his arm, making his way toward the station.

Acheson walks toward Truman.

Acheson

Mr. President, welcome back to Washington.

Truman

(Surprised. Adjusting his glasses) Mr. Acheson?

Acheson

Most certainly is sir.

Truman

(Truman smiles). Well, I don’t see any brass bands playing Dean. Wasn’t expecting much of a welcome after the drubbing we just took from the Republicans. First time in 16 years they’re going to control Congress. Imagine a lot of Democrats are going to be pointing the finger at me.

Acheson

(Attempting to push back). Mr. President, there were lots of reasons why……

Truman

(Nicely waves him off). No, no, no Dean . . . they might be right. It was a losing campaign and I’m the head of the party.

But we’ll sort that out later. One thing I am certain of Dean is how much I appreciate you being here to greet me – more than you know.

Truman’s demeanor lightens.

Say, could I interest you in coming back with me to the White House for a little bourbon ‘libation’? ‘Old Grand-Dad’ happens to be a valued member of the Truman family. I think I could use his company right now – and yours, if you have the time.

Acheson

I’d be delighted to Mr. President. I’m always at your disposal.

They walk off together.

Acheson then appears on one side of the stage and speaks to the audience.

Acheson

For years it had been a Cabinet custom to meet President Roosevelt on his return from happier elections and escort him to the White House. It never occurred to me that after this less-than-happy outcome President Truman would be left to creep unnoticed back to the capital. So, I met his train. I thought it only proper and fitting that I be there.

To my surprise and horror, I found that I was alone on the platform where his car was brought in. Both the office of the president and the man deserved much better than that.

Truman appears on the other side of the stage and speaks to the audience.

Truman

Quite frankly, I was somewhat astonished to see Dean on the platform to greet me. I fully expected Democrats and not a few members of my administration to make themselves scarce in the days following the humiliation of the election.

So, Dean’s gesture of loyalty and respect was something I would never forget. It helped forge an iron bond between us that would only strengthen during our years in office together – and well beyond.

PROLOGUE ENDS. Stage dark.

SCENE 1 INAUGURATION DAY JANUARY 1953

Sounds – “Hail to the Chief”.

On the screen, Inauguration Day, January 1953.

Then b & w film footage from the Eisenhower inaugural, starting w/ President and Mrs. Truman walking out of the White House North Portico entrance to greet the President-elect and Mrs. Eisenhower, who have arrived by open limousine. Next in succession comes the motorcade to the Capitol, seating of dignitaries (including Harry and Bess), the swearing-in and close of ceremonies (Ike’s ‘So help me God’, sounds of the 21-gun salute to the new president). Again “Hail to the Chief” is heard – and fades out.

Stage lights up, reveal the Achesons’ drawing room at their home at 2805 P Street in Georgetown. Outside a large, cheering crowd can be heard, with shouts of “We want Harry!” and “Good luck Harry!”

In attendance in scene: Harry and Bess Truman, Dean and Alice Acheson.

Truman is looking out a window with Acheson listening to the crowd (their backs to audience). He then steps out on a little terrace in front to thank them — speaks loudly to be heard.

Truman

Smiling broadly, waving.

Thank you, thank you for being here.

I appreciate this more than any meeting I ever attended as President, Vice President or Senator – especially since I’m now just plain Harry Truman, private citizen!

More cheers from crowd.

Truman

Should tell you I just had my first taste of civilian life.

On our way over here from the Capitol we were just inching along. Lots of traffic. Then I noticed the White House car we were in was obeying all traffic lights. Imagine that! First time in years I’ve had to stop for a red light!

Laughter from crowd.

Truman

But Bess and I will get used to it!

Its good to be Citizen Truman again!

Thank you again for coming out!

Cheers continue from crowd.

Truman waves again and steps back inside. Rejoins Acheson and they turn and sit down with Bess and Alice in drawing room to exchange a few reminiscences before they join the other guests for the luncheon.

Truman

Dean and Alice, Bess and I can’t thank you enough for arranging this luncheon at your home – and for turning out this great crowd!

Acheson

We had nothing to do with the crowd, Mr. President. They heard you would be here and showed up of their own volition. All volunteers! Georgetown is having its own farewell party for you, a special favorite.

Harry and Bess exchange smiles. Acheson pauses, then asks:

So, Mr. President, how was the ride up to the Capitol with Ike?

Truman

Bit chilly Dean. Barely spoke to each other. We kept it general – on the crowd, the pleasant day, the orderly transfer. I think Bess got the better deal, driving up with Mamie in car No. 2.

Harry smiles, then turns more serious.

I do have to say that we were disappointed that the Eisenhowers did not accept our invitation to lunch or even to come in for a cup of coffee before we went up to the swearing-in. That’s been a tradition stretching back to 1809 when Madison called on Jefferson. But Ike just stayed in the car waiting for us to come out.

Mrs. Truman

Actually, Harry was furious. Apparently, Gen. Eisenhower did not want to step inside the executive mansion until he was the executive.

Truman

That’s what they say. (pause, then continues)

Truth is our relations soured during the campaign, especially after Ike didn’t defend Gen. George Marshall from attacks by that gutter snip (Truman spits out his name) Senator Joseph McCarthy, a pathological liar.

McCarthy said Marshall was soft on communism – even called this great and honorable American a “traitor.” Ike should have stood up to him, but didn’t — political reasons. McCarthy had the Republican party and a lot of others cowed. Nobody wanted to cross him.

Acheson

That was certainly one of the lowest points in the campaign.

Truman

Sure was, but once the election was over, I tried my damnest to make the transition as smooth and efficient as possible.

I invited Ike and his top aides to a briefing in the Cabinet room on the state of the world. Dean, you were there.

Acheson

Gen. Eisenhower’s attitude perplexed me. His good nature and easy manner were gone. He seemed embarrassed and reluctant to be with us. He chewed on the earpiece of his glasses and occasionally would ask for a memorandum on something that caught his attention.

But mainly he just sunk back in the chair facing you. I think you described his demeanor as “frozen grimness.”

Truman

That about summed it up. After that meeting I was very troubled. I had the feeling that the President-elect had not grasped the immense job ahead of him.

Truman pauses, then resumes.

You know, one reason I wanted to spend more time with Ike was because I kept thinking about how little time I had with President Roosevelt before I took over the job.

I met with him exactly two times – two times — from the time we got sworn in on January 20 to the day he died in Warm Springs 82 days later. And both of those times nothing of consequence was discussed. He never even told me about the atomic bomb we were building.

Again, Truman pauses, deep in thought.

I was about as unprepared to take on the duties and responsibilities of president as anyone could be.

I remember telling a few reporters that when I was told what had happened to the president, “I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me.” I also said: “Boys, if you ever pray, pray for me now.”

Somber room. Acheson responds.

Acheson

You got a lot of prayers, Mr. President, including from everyone here today.

Truman

I know Dean. Those prayers helped.

Anyway, I was plenty scared. But scared or not, prepared or not, I promised myself one thing: that I’d work damn hard to be a good president.

And I’ve learned that any man who sincerely tries to live up to the responsibilities of the office cannot keep from growing in the presidency.

I also knew I had to get the best people to work with me.

I still remember the day I asked you to become my next secretary of state.

Acheson

Oh, so do I. You asked me to join you at Blair House. When I came in you said I’d better be sitting down when I heard what you had to say. That got my attention!

Truman

As intended.

I said: Dean, I want you to be my Secretary of State. To my great amusement, you were utterly, totally speechless – a rare occurrence I might add!

And then you said you were not qualified to meet the demands of the office in the unprecedented times we were living in. Those were your words.

Acheson

They were – and I meant every word. Still do!

(The two are having fun batting back and forth).

Truman

I responded that was undoubtedly so, but then I could say the same for myself, or any man. The question was whether you would take the job!

Acheson

But before I could answer, you told me to go home, talk it over with Alice, and no one else, and call you in the morning.

Then you reiterated “no one else” because you said you wanted to see whether — for once — a secret could be kept in the city of Washington!

Next day I called, said that Alice cheerfully agreed, and I would be at your service.

Then a minor Washington miracle followed – no leak occurred even though the public announcement was not made until six weeks later.

Truman interjects.

Truman

And that record still stands!

Laughter among all. With lighter banter established, it continues.

Mrs. Acheson

Mr. President, Dean told me that one of the little known things you did after you took office was to order a change in the presidential flag and seal.

Truman

Sure did Alice. Hadn’t been done since Woodrow Wilson was president.

The eagle on the old flag and seal was looking at the arrows for war. I thought it was high time for that eagle to be looking at the olive branch for peace and gazing forward.

The two World Wars were over. We needed finally to be looking ahead!

Acheson

But you remember, Mr. President, what Winston Churchill said to you about that change you ordered – he thought the eagle’s head should be on a swivel!

All laugh.

Mrs. Acheson

You also made a few changes in the White House itself.

Mrs. Truman

Well, that’s an understatement Alice!

Harry added what’s now called the Truman balcony but that wasn’t enough for him. Oh no. Then he decided to gut the entire mansion.

Everyone laughs again.

Truman

Had to be done Bess. There hadn’t been any major work done on the mansion since ole Andy Jackson.

Teddy Roosevelt pulled out a load-bearing wall and Silent Cal Coolidge added some concrete to the roof, but the place was rotten and falling apart.

I first noticed it when I was downstairs in the East Room listening to a performance by the pianist Eugene List. I looked up and saw the chandelier quivering – it was hanging on by a thread. Could have wiped out me and the cabinet in one fell swoop!

Mrs. Truman

Another clue was when the leg of our daughter Margaret’s piano broke through the floor of her sitting room. Harry concluded that the second floor was staying up mostly out of habit!

Truman

I also worried about my private bathroom where one of the supporting rods had been run though the floor to the toilet.

This thing really scared me. I was convinced that one evening I’d be sitting in there and pull the plunger and wind up in the State Dining Room (pauses) and the Marine Band would be playing ‘Hail to the Chief’ as I come though the ceiling!

Everyone cracks up.

Outside they can hear more cheers: “Don’t go Harry! “We’re going to miss you Harry!”

Mr. President, I think its time we join our guests for the luncheon. This has been most enjoyable!

The four stand up. As they do Acheson asks:

Acheson

Any parting wisdom you’re going to leave with us?

Truman

Well, I certainly don’t intend to make a speech.

I’ll bet that’s not what people came for!

But, Dean, there are a couple of things I’d like to say that might qualify for presidential wisdom.

One thing you have to remember when you get to be President is that all those things, the honors, the twenty-one-gun salutes, Hail to the Chief — all those things aren’t for you. They’re for the presidency. If you can’t keep the two separate, you’ll find yourself in all kinds of trouble.

The other thing is that the President of the United States hears a hundred voices telling him that he is the greatest man in the world. He must listen carefully indeed to hear the one voice that tells him he is not.

Mrs. Truman

And Harry is not just referring to his wife.

Laughter from all.

Truman

Bess should know!

Turns back to Acheson.

Dean, I’m also going to say something about you.

As I’ve told you before, I consider George Marshall the greatest American of our time. But I regard you as my greatest Secretary of State and one of the greatest in U.S. history. Whatever I accomplished could not have been done without you at my side. You’ve been my strong right arm.

Acheson

You are too kind, Mr. President.

Truman

As you have been to me, Mr. Secretary.

Oh, (with twinkle in his eye) I might also share with our luncheon companions a little something I’ve learned over the years in Missouri and here in Washington.

Three things can ruin a man — power, money, and women.

He turns to Bess, who smiles knowingly. She’s heard this one before and knew it was coming. Truman resumes –

Now, I never wanted power.

I never had any money.

And the only woman in my life is the one standing next to me right now! (T, 181)

And after this wonderful get together, we’re off to Union Station and back to our home in Independence.

Pause – then Truman continues with emphasis:

And, as we like to say in Missouri, that’s all there is to it!

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark.

SCENE 2 “THAT’S HIS JOB”

“That’s his job” appears on screen.

Spotlight comes on to reveal Truman on the left front of the stage, sitting at his desk in his study at home in Independence. He finishes writing a letter, looks it over, and then reads it aloud.

Truman

Dear Dean:

There are not enough words in the dictionary — on the favorable side, of course — to express the appreciation that Mrs. Truman and I felt for your wonderful luncheon on the twentieth. I never have been at a function of this sort where everybody seemed to be having the best time they ever had. It is one of the highlights of our trip to ‘Washington and back.’

Please express our thanks and appreciation, with all the adjectives you can think of, to Mrs. Acheson.

Pauses, thinking of the best way to express his next thought, then reads with emphasis.

I hope that we will never lose contact!

Most sincerely, Harry

Truman looks again at the letter and decides to add a postscript.

P.S. I’ve had some sixty thousand letters and telegrams since I left office – 99.4% favorable! Believe it or not. You’ve never seen as much crow eaten, feathers and all.

Spotlight off Truman; shifts to Acheson on the right front of the stage. He is dressed casually, in his study at his Georgetown, P St. home. He’s reading over his reply letter.

Acheson

Dear Mr. President,

Thank you for your letter I can’t tell you how pleased I was to receive it.

You and Mrs. Truman have been constantly in our thoughts these last few weeks. We talk about the great epoch in which you permitted us to play a part and which now seems ended in favor of God knows what.

Now, I am happy to report to you that I’m fully engaged in the withdrawal phase of what I call “the habit-forming drug of public life.” Alice is in charge.

At our farm ‘Harewood’ she has me painting the porch furniture, wheel barrowing manure for her roses, and taking the grandchildren down to the next farm to see horses, cattle, pigs and puppies.

Aside from that I just lie around all day, mostly reading, with swimming and some moderate use of alcoholic beverages.

I highly recommend!

Affectionately, Dean

Spotlight returns to Truman in his study. Truman chuckling then reads his latest to Acheson.

Truman

Dear Dean,

Please tell Mrs. Acheson not to work you too hard; I am afraid she will set a bad example and I, myself, will get into trouble with my Boss.

Truman pauses. Leafs through a few items on his desk. His demeanor turns more contemplative.

Dean, have been giving a lot of thought to my life as an ex-president. (With emphasis) What shall I do? Been going over a book on what former Presidents did in times past. Maybe I can get some ideas.

I do know one thing. I don’t want to be an ‘elder statesman’ politician. I like being a nose buster and an ass kicker much better and reserve my serious statements for committees and schools!

Most sincerely, Harry

Spotlight returns to Acheson as he gets up from his desk and walks to center stage. Speaks to audience.

Acheson

Harry Truman’s nearly eight years in the presidency were tumultuous. Through it all he was not in the eye of the storm, he was the eye of the storm.

Think for a moment of the magnitude of just three of the decisions he made during this time.

He dropped the atomic bomb on Japan to end World War II.

He was the first world leader to recognize the new state of Israel, to prevent another Holocaust of the Jewish people.

And, he fired America’s most popular military commander, Douglas MacArthur, during the height of the Korean War because of the general’s challenge to a bedrock of our Republic — civilian control of the military.

Harry Truman thought that the greatest part of the president’s responsibilities was making decisions. Papers may circulate around the government for a while but they finally reach his desk. And then, there’s no place else for them to go. He can’t pass the buck to anybody.

“A president has to decide”, Truman would say, “no one else can do the deciding for him – (with emphasis) that’s his job.”

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark.

Scene 3 DROPPING THE BOMB

Sound of aircraft engines starting is heard.

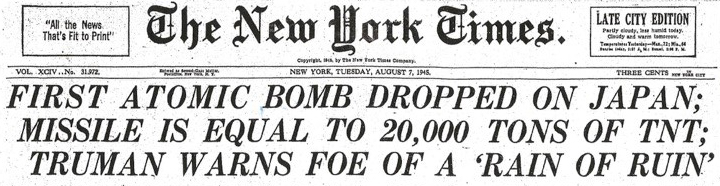

On the screen, Dropping the Bomb 1945 appears.

Then audience sees b & w film footage of the atomic bomb being loaded onto the ‘Enola Gay’, then takeoff and drone of engines as bomber is in flight to Hiroshima, followed by detonation of the ‘Little Boy’ bomb and its mushroom cloud – can hear in background sound of Truman’s voice announcing that a formidable weapon had been used – then scenes of destruction in Hiroshima followed by footage of the Japanese surrender ceremony aboard the USS Missouri.

Lights on stage dim. Spotlight comes up on the side of the stage where a ‘Hiroshima official’ appears and reads the following:

Hiroshima official

Dear Mr. Truman:

As Chairman of the Hiroshima city council, I have the honor of bringing to your attention a resolution adopted by the city council on February 13, 1958, in connection with the statement you recently made concerning the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

RESOLUTION NO. 11

The citizens of Hiroshima — who have led their life in suffering because of the more than two hundred thousand lives sacrificed — consider it their sublime duty to hold that no nation of the world should ever be permitted to repeat the error of using nuclear weapons an any people on the globe, whatever be the reason.

If the recent statement made by Mr. Truman be true that he felt no compunction whatever after directing the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and that hydrogen bombs would be put to use in the future in case of an emergency, it would be a gross defilement committed on the people of Hiroshima and their fallen victims.

We, the city council, do hereby protest against this statement in deep indignation and appeal to the wisdom of the United States and her citizens to fulfill their obligation for the cause of world peace.

Lights up. Truman walks on stage and proceeds with the Hiroshima official to take their chairs at center stage. A small table separates them, with a pitcher of water and glasses.

Truman

Mr. Chairman, I’ve mulled over your letter and the resolution for some time and I welcome the opportunity we now have to discuss its contents in person. You and the people of Hiroshima deserve to hear directly from me on these matters.

First, let me say that the feeling of the people of your city is easily understood, and I am not in any way offended by the resolution that the city council passed.

Hiroshima official

Thank you, President Truman. Most appreciated.

Truman

That said, Mr. Chairman, it becomes necessary for me to remind the city council, and perhaps you also, of some historical events.

We had been at war for three and a half years, at a terrible cost to both sides. My military advisers informed me that to end the war it would require at least a million and a half soldiers to invade the Japanese homeland. Likely casualties were around a quarter of a million Americans and at least an equal number of Japanese.

The atomic weapon was built to end the war. I therefore made the decision to authorize the use of the bomb to bring this brutal war to a swift conclusion.

I think the sacrifice of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was urgent and necessary for the prospective welfare of both our countries.

Hiroshima official

But why were we not given any warning that such a powerful weapon would be used?

Truman

You were.

We issued a public ultimatum just days before the bomb was dropped calling on Japan to surrender, an unconditional surrender. The alternative, we said, was prompt and utter destruction. It was reported on Japanese radio. Our planes dropped millions of leaflets over your cities with a translation of the ultimatum.

The document evoked only a very curt and discourteous reply. Your prime minister said it was beneath contempt.

It was only after that that I gave the final order saying I had no qualms if millions of lives could be saved.

Hiroshima official

There were many in Japan who knew we were already defeated, finished. It was just a matter of time before we would have to surrender. Didn’t you know this?

Truman

We’ll never know. But what we knew at the time suggests otherwise. No one thought you were about to quit. During the whole war, not a single Japanese unit had surrendered.

Truman pauses.

And, Mr. Chairman, a brutal certainty remains. Japan was unable to muster the political will to quit until after both atomic bombs had been dropped.

Hiroshima official

Shouldn’t you have given more time between the use of the two bombs? Why didn’t you wait for us to fully absorb the totality of the destruction of the Hiroshima bomb before you gave the go ahead for bombing Nagasaki?

Truman

Mr. Chairman, I did not make an additional decision concerning the second bomb. The initial military directive I approved was for the first bomb and for additional bombs to be delivered to the approved targets as soon as they were ready. This could be stopped only by Japanese agreement to surrender unconditionally.

Tragically, after Hiroshima, there was no word from Japan, no appeal for mercy or sign of surrender.

Now the day after the Nagasaki bombing we did hear from Tokyo. I ordered no further use of atomic bombs without my express permission. One more bomb was available at the time. The thought of wiping out another city of 100,000 people was too horrible.

Hiroshima official

Once you learned about the total devastation of the bomb on Hiroshima – the 75,000 killed, mostly civilians, all the injured, the effects of the radiation – did you not feel any regret about your decision?

Truman

Hell yes! I’ve had a lot of misgivings.

I knew it was a decision that no man in history had ever had to make. It was terrifying to think about. But it was a decision that had to be made.

And, thank God, in a matter of days, Japan gave up. The killing stopped. As I’ve said, my object was to save as many American lives as possible but I also had a humane feeling for the women and children of Japan, all those kids.

But let me remind you of one thing, Mr. Chairman, and I will be blunt. The need for such a fateful decision never would have arisen had we not been shot in the back by Japan at Pearl Harbor in December, 1941.

In spite of that shot in the back, this country of ours, the United States of America, has been willing to help in every way the restoration of Japan as a great and prosperous nation. And today our countries – our democratic countries – stand side-by-side.

Hiroshima official

For that, President Truman, we do thank you and the American people.

The two men stand, the Hiroshima official does a slight bow – they shake hands and the official walks off the stage.

Acheson then comes on stage to join Truman. Their remarks are directed to the audience.

Acheson

I had no doubt that the President’s decision to use the bomb was the right one. It would end the war. No country could stand up to it. And, quite frankly, the American people would not have tolerated a president who refused to use a weapon that would shorten the agony of the war.

Regarding the horrific destruction of Hiroshima, my reaction was one of horror. I thought then if we could not work out some sort of organization of great powers to control this weapon, we would be doomed.

I later sent a letter to the president saying – I have a copy here – [Acheson reads] “This scientific knowledge of the atom relates to a discovery more revolutionary in human society than the invention of the wheel. If the invention is developed and used destructively there will be no victor and there may be no civilization remaining.”

Truman

I fully realized the tragic significance of the atomic bomb. The destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was lesson enough to me.

That’s why I called for international arrangements that could include the renunciation of the use and further development of the atomic bomb. I thought that unless the United States took this path, a desperate armaments race would follow – which is exactly what happened with the Russians.

As for the bomb, it will always remain my prayer that there will never again be any need to invoke its terrible destructive powers.

And for those who follow me in the presidency, I can only say it is an awful responsibility that has come to us. We must all understand that starting an atomic war is totally unthinkable for rational men.

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark

SCENE 4 RECOGNIZING ISRAEL

Somber violin music is heard.

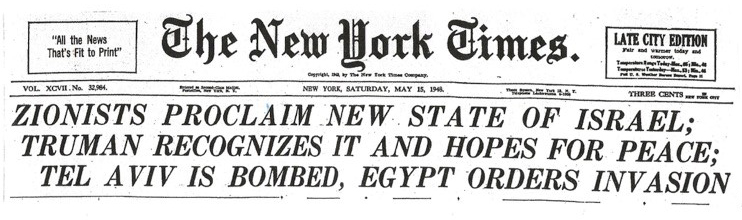

On the screen, Recognizing Israel 1948 appears.

Followed by film footage of the liberation of Nazi concentration camps and Holocaust survivors. Then footage of Jewish European refugees boarding ships and arriving in Palestine. Scenes of British mandate security forces policing Jewish settlers and the local Arab population. Scenes of violence, including King David Hotel bombing.

The cascade of images freezes at this point.

Stage lights up. The setting is the Oval Office with Truman siting behind his desk. In a semi-circle in front of him are the then-Secretary of State, Gen. George Marshall, accompanied by Dean Acheson; the Secretary of Defense James Forrestal; and Clark Clifford, Truman’s special counsel on his White House staff.

Truman opens the meeting.

Truman

Gentlemen, I’ve asked you here this afternoon because in exactly two days and two hours time (Truman points to his watch), on May 14, all hell could be breaking loose in the Middle East.

The British mandate for Palestine is set to expire. They’ve had it. They’re pulling out and turning the whole thing over to the United Nations to sort out.

Fighting between Arab Palestinians and Jewish immigrants is intensifying. We’ve been pushing the idea of a truce, but no one’s buying it.

Right now Jewish forces have the upper hand and they plan to proclaim an independent state – the state of Israel — at the stroke of midnight on the 14th.

So how do we respond? Do we recognize the new Jewish state? I need your best advice and recommendations.

I know there are strong views on this subject – and I want to hear them all, unvarnished. Don’t paper anything over. We don’t have time for that. Then I’ll make a decision.

Gen. Marshall, I know the State Department is most concerned about how the Arabs would react to the proclamation of a Jewish state.

Marshall

Yes, that’s right Mr. President. Let me elaborate.

There are basically three reasons why my colleagues and I at State believe that recognition of Israel at this time would be ill-advised and contrary to our national interest.

First, the establishment of a Jewish state would lead to protracted war with the Arabs and the long-term destabilization of the Middle East.

Second, it could lead to American military involvement there, something our military leaders are most concerned about. I’m sure Sec. Forrestal will expand on this.

And third, we think there is a possibility that if the Arabs are antagonized, they will go over to the Soviet camp. The Kremlin has long desired to gain a foothold in the Middle East. This could be the occasion.

Given these concerns, Mr. President, we believe we should continue working at the United Nations for a solution that both the parties can agree to and not make any decision on recognition at this time.

Truman

Thank you General. I would just say here that your concern that the Arabs could make common cause with Russia is one that I have not lost sight of. I’m sure the Russians would welcome the Arabs into their orbit.

Secretary Forrestal, your views?

Forrestal

Thank you Mr. President.

General Marshall is correct. Our military leaders feel strongly that no action be taken that would further commit U.S. armed forces. We are already stretched very thin in Europe and elsewhere countering the Soviets. We would not be able to send troops to Palestine if trouble should break out there. And trouble is going to break out.

There are about 400,000 Jews in Palestine surrounded by forty million Arabs. Forty million Arabs are going to push 400,000 Jews into the sea. So, what do we do then?

If we recognize Israel, Mr. President, we would be playing with fire while having nothing to put it out with.

Our military leaders are also very alarmed about the oil resources of the Middle East and the critical need for Saudi oil in the event we find ourselves in another shooting war. This is a vital security interest.

I need not remind you, Mr. President, that hostile Arabs might deny us access to their petroleum treasures.

Oil, Mr. President, that is the side we ought to be on.

Truman interjects, clearly perturbed with Forrestal’s last comment.

Truman

Secretary Forrestal, I will handle this situation in the light of justice, not oil.

I will also remind you that I have repeatedly said that U.S. armed forces would not be used to enforce peace in Palestine. I’m not going to send 500,000 American soldiers there to make peace.

Truman lets his rejoinders to Forrestal sink in for a moment then turns to Clifford.

Now, I’ve asked my special counsel Clark Clifford to join us and argue the case for recognizing Israel and the timing for doing so.

Clark, please proceed.

Clifford speaks in a calm, orderly, unhurried manner.

Clifford

With all due respect, Mr. President, I believe American policy has lost touch with reality.

As you’ve mentioned, a truce is unlikely. The fact is that a Jewish homeland in Palestine is already being established, on the ground, by the thousands of refugees.

So, a separate Jewish state is inevitable. It will be set up shortly. We must recognize it eventually. Why not now?

Recognition would be consistent with U.S. policy. You’ve said many times that you supported a Jewish homeland in Palestine, a goal the British government formally endorsed in the 1917 Balfour Declaration.

You’ve also said that that declaration is in keeping with President Woodrow Wilson’s noble principle of “self-determination.”

Recognition would be an act of humanity, everything this country should represent. The murder of 6 million Jews by the Nazis was one of the greatest tragedies of all time. Every thoughtful human being must feel some responsibility for the survivors.

We also know that popular support in the U.S. for a Jewish homeland is overwhelming, and not just among Jewish Americans and Zionists. Forty governors and more than half the Congress have signed petitions urging your support.

So, for all these reasons Mr. President, I believe the time to act is now. Unfortunately, the State Department has no policy except to wait on events.

We have therefore prepared a statement that we propose you read at a press conference tomorrow urging the establishment of a Jewish state and promising immediate recognition.

As Clifford is speaking, Gen. Marshall’s ‘body language’ makes it obvious that he is not pleased with what he is hearing.

As Clifford concludes, Marshall immediately responds. He is agitated.

Marshall

Mr. President, I thought this meeting was called to consider an important and complicated problem in foreign policy. So, I don’t even understand why Mr. Clifford is here.

He is a domestic adviser, and what we’ve just heard from him is just straight politics. He is pressing a political consideration with regard to this issue and I don’t think politics should play any part in this.

Truman

Gen. Marshall, Mr. Clifford is here because I asked him to be here. There are many dimensions to the decision I have to make and I want to hear them all.

Acheson

Mr. President, may I address a point made by Mr. Clifford?

Truman

Go ahead Mr. Acheson.

Acheson

I must take issue with what he said – and what you’ve said – about the Balfour Declaration going hand-in-hand with Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self-determination.

It seems to me that if there is one principle in the world that was absolutely and directly violated by the Balfour Declaration it was the principle of self-determination.

Self-determination would entitle Arabs currently living in Palestine to decide whether they wanted to be inundated by hundreds of thousands of Jewish immigrants. Instead, what is being done is to bring the Jews in over the objections of the Arabs. However noble and humanitarian that policy may have been, it certainly is not one justified by self-determination.

There is a pause here. Truman is considering Acheson’s remarks, then responds.

Truman

Here we will have to disagree Dean. I would also add that my own reading of the complicated history of the Fertile Crescent and the Bible make me a supporter of the idea of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. As you know, it was once the ancient kingdom of Israel.

Even more to the point, when we think about displaced persons, everyone else who’s been dragged from his country has some place to go back to, but the Jews have no place to go.

But I do have one concern. I fear very much that the Jews will be like all underdogs. When they get on top they are just as intolerant and as cruel as the people were to them when they were underneath. I would regret this very much because my sympathy has always been on their side. What I am trying to do is make the whole world safe for the Jews.

Truman moves to wrap up.

With that, gentlemen, I think we should bring this meeting to a conclusion. I thank you for your views. Any final comments you’d like to make?

Silence, then Gen. Marshall speaks.

Marshall

Mr. President, I feel compelled to underscore a point I made earlier.

Domestic political considerations must not determine our foreign policy.

To follow Mr. Clifford’s advice on recognition would be to subordinate an international problem to domestic politics. Any premature, ill-advised recognition of the new state would be disastrous to American prestige in the United Nations and appear only as a very transparent bid for Jewish votes in the upcoming November election. It would also diminish, in my view, the great office of the President.

Indeed, (Marshall looking intently at Truman) if you proceed down the path as proposed by Mr. Clifford and if, in the upcoming presidential election, I were to vote, I would vote against you.

The room goes stone silent. After several moments pass, Truman responds. He shows no signs of emotion. His expression, as it has been throughout the meeting, remains fixed. He raises his hand briefly when he starts to speak.

Truman

Gentlemen, I am fully aware of the difficulties and dangers involved with this situation, to say nothing of the political risks I will run. I am prepared to accept them.

Lights on Oval Office meeting go dark.

At each end of the stage Acheson and Truman appear and speak directly to the audience.

Acheson

Eleven minutes after Israel was proclaimed a state on May 14, 1948 the White House released a statement announcing President Truman’s decision – the United States would be the first country to offer de facto recognition of the new Jewish state.

The next day Arab armies invaded Israel and the first Arab-Israeli war began.

Harry Truman would later say the most difficult dilemma he faced as president was what to do about Palestine. He was pulled in many different directions. Among his top foreign policy and military advisers he was alone in supporting recognition of Israel. But for him, as he would later say, it was “a basic human problem.”

Gen. George Marshall, who Truman so admired, did come around to supporting U.S. recognition of Israel because, Marshall said, “it was the President’s choice.”

Truman

I am proud to this day that it was the United States of America that was the first to recognize the birth of the new state of Israel.

The fate of the Jewish victims of Hitler was a matter of deep personal concern to me. The moral issue was paramount. As President I undertook to do something about it.

Let me also add this – and do something I rarely do – indulge in a ‘what might have been.’

Before the proclamation of the state of Israel, a partition plan had been drawn up by the UN, which I supported. Palestine would be divided into two separate states, one Jewish and one Arab. They would be tied together in an economic union, with an international zone around Jerusalem to guarantee access by all faiths to their holy sites.

Jews welcomed the plan. They would get their homeland. But the Arabs did not like it and said it would be carried out over their “forceful opposition,” meaning over their dead bodies. They keep their word on that.

I believe this was a great missed historic opportunity. I was hopeful then – maybe naively — that this plan could open the way for peaceful collaboration between Jews and Arabs. I knew it would be difficult, but with the economic union the UN proposed they might eventually work side by side, as neighbors.

Well, that hasn’t happened. But I still believe it could and should.

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark

SCENE 5 FIRING MacARTHUR

Sounds of Korean War fighting are heard in the distance then grows louder.

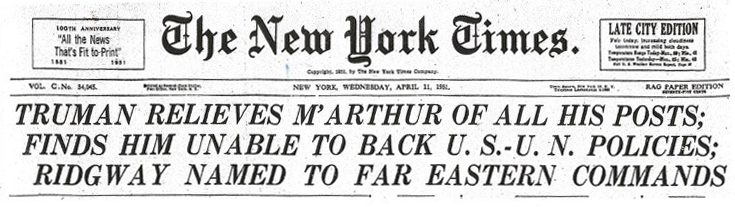

On the screen, Firing MacArthur 1951 appears, followed by newsreel footage from the Korean War including faces and scenes of soldiers in combat, the Truman-MacArthur meeting on Wake Island, and ending with multiple shots of MacArthur in the field, then freezes on close-up with his iconic corncob pipe.

Stage lights up and the audience sees a wartime conference room with three large maps on easels showing battle lines and arrows indicating troop movements in and around the 38th parallel dividing North and South Korea.

Sitting at the conference table are Truman, Secretary of State Acheson and the newly appointed Secretary of Defense

George Marshall. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Omar Bradley, is standing at one of the easels with pointer in hand briefing the group on the latest battlefield situation.

Bradley

Mr. President, the Chinese People’s Liberation Army suffered high casualties in our latest encounter. They are re-grouping. The 8th Army and the 10th Corps are located here and here. We are concerned about our extended supply lines here, running southwest to northeast across Korea. Our air support is…

As he continues his briefing, a White House aide enters the room.

Aide

Mr. President, apologies for interrupting but we just received a copy of a letter that you need to see.

Truman takes the letter and reads it. Grimaces as he does so. Puts the letter down on the table, and turns to the group.

Truman

General Bradley, please take your seat. We need to turn to a more immediate matter.

There has been another pronouncement about the conduct of the war from our supreme allied commander in the field, General Douglas MacArthur. This time in the form of a letter to Representative Joseph Martin, the minority leader in the House.

Truman picks up and reads from MacArthur’s letter.

“Dear Congressman Martin:

It seems strangely difficult for some to realize…”

Truman looks up from letter:

Clearly he’s pointing his finger at me.

He returns to the letter:

“….to realize that here in Asia is where the Communist conspirators have elected to make their play for global conquest. If we lose the war to communism in Asia the fall of Europe to communism is inevitable, win it and we preserve freedom.

As you point out, Congressman, we must win. There is no substitute for victory.

Faithfully yours, Douglas MacArthur”

Well, gentlemen, I’m glad the general is faithful to Congressman Martin – he’s sure as hell not faithful to his Commander-in-Chief. With this language he’s trying to provoke us into a full-scale war with China, a World War III.

And that’s what a lot of people have never understood. Ours was going to be a police action in Korea, a limited war, whatever you want to call it, to stop aggression and to prevent another catastrophic global war.

That has been my highest order of business. I don’t know why some people, including MacArthur, could never get that through their thick heads.

Acheson

This is vintage MacArthur, Mr. President. He believes a theater commander should be allowed to act independently, with no orders from the President, the United Nations, or anyone else.

Truman

That’s the nub of the problem Dean, and why I’ve called him “Mr. Prima Donna, Brass Hat, Five Star MacArthur.” He’s always playing to the galleries, sending statements down from ‘on high’– his ‘pronunciamentos.’

Acheson smiles. Truman’s comment lightens up the discussion, but only for a moment.

Marshall

Mr. President, there have been many serious disputes between MacArthur and Washington about his orders. At various times the subject of relieving MacArthur of his command has come up. Are we at that point now?

Truman

I’m going to get to that General Marshall, but let me say this first.

When I got into a position of power I always tried to keep in mind that just because I saw something in a certain way didn’t mean that others didn’t see it in a different manner. That’s why I always hesitated to call a man a liar unless I had the absolute goods on him.

So, with General MacArthur, who we all know and respect as a great war hero, I tried to place myself in his position and tried to figure out why he was challenging the traditional civilian supremacy in our government.

That’s why I took that 7000-mile trip to Wake Island – to sit down with him face-to-face. I thought we could reach some kind of understanding.

Acheson

An admirable undertaking, Mr. President, with little prospect for success.

Truman

I understood that Dean. I never underestimated my difficulties with MacArthur, but after the Wake Island meeting – which only lasted a few hours in the morning — I hoped that he would respect the authority of the President.

Hell, he didn’t even have the good manners to stay for lunch. Said he had to get back to overseeing the war effort. (Pauses) I told him that was my job.

Acheson

Yes, and after that – despite his assurances to the contrary – the Chinese entered the war by crossing the Yalu. This led to the worst defeat of U.S. forces since the battle of Bull Run in the Civil War.

And not long after that he released a statement threatening China with an ultimatum – threatening the full preponderance of Allied power might be brought to bear against it, including, one would presume, the atomic bomb.

Now that set off alarm bells. Capitals all over the world wanted to know: What does this mean? Is there about to be a shift in American policy?

At State we were almost wild by this time because no one at the Pentagon could explain what MacArthur was thinking of. All of this was entirely at cross-purposes with what you were saying.

Acheson pauses, then states forcefully:

Mr. President, MacArthur has been insubordinate; his insubordination has done the country vast harm and risks involving us in wider warfare. He has to go.

Truman

Thank you Dean.

Gen. Marshall, your recommendation as Defense chief?

Marshall

Mr. President, I am in agreement with Secretary Acheson’s views on Gen. MacArthur and concur with his recommendation.

I recently reviewed the messages that have gone back and forth with MacArthur — both before and after your Wake Island meeting — and have concluded that he should have been fired two years ago.

Truman

General Bradley, where do the Joint Chiefs stand?

Bradley

Mr. President, the Chiefs flatly reject Gen. MacArthur’s call for a wider war with China. The kind of “victory” he has in mind – victory by bombing Chinese cities, victory by expanding the Korea conflict to all of China – would involve us in the wrong war, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.

Our unanimous judgment is that General MacArthur should be relieved of his duties.

I should also add that, in our view, if MacArthur knew in advance he was going to be fired, he would probably resign.

Truman quickly responds:

Truman

General Bradley, the son-of-a-bitch isn’t going to resign on me, I want him fired.

General MacArthur has openly opposed my orders as President and Commander in Chief. If I allow him to defy civil authorities in this manner, I myself will be violating my oath to uphold and defend the Constitution. I will not tolerate his insubordination any longer.

Truman pauses, collects himself, and speaks directly to Bradley.

General Bradley, I am now directing you to prepare the orders that will relieve General MacArthur of his command, effective immediately.

Truman notices that Acheson wants to speak.

Dean, you have something else to say?

Acheson

I would only add, Mr. President, that if you take this step, you will have the biggest political fight of your administration.

There will heavy shelling from the press and Congress.

Given his popularity, the general will return home to a hero’s welcome. The country will be behind him, not you.

Most likely he will be asked to speak before a Joint Session of Congress and much of the country will be watching on television.

It will be one helluva time.

Truman

I expect this, Dean. I fully expect this.

Thank you gentlemen for your candor – and your support.

Lights down. Archival film comes up on scrim of MacArthur’s ticker tape parade in New York City, snippets of his address to the Joint Session of Congress (including old soldiers ‘fade away’ closing line) and standing ovations, perhaps comments by Members of Congress or public afterwards.

Film clips ends, Truman walks on stage.

Truman

Well, MacArthur’s return, the ticker tape parade in New York, that speech before Congress, certainly set off a wave of emotion and a great deal of oratory.

There were some 30 ovations for his speech. One Congressman was so overcome he shouted: “We heard God speak here today, God in the flesh, the voice of God!”

I didn’t listen to the speech or watch it on the television but I did read it. I told a few people afterwards I thought it was a bunch of damn bullshit.

Excuse my language. But I felt as strongly about this as anything I dealt with during my presidency.

Civilian control over the military is a bedrock of our republic. It goes back to Washington. No one, no one has ever challenged this and gotten away with it. It wasn’t going to start with me.

Anyway, I figured sooner or later the American people would get wise to MacArthur – their good sense and judgement would prevail — and the old general would fade away – just as he said he would.

And that’s what he did.

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark.

Scene 6 YALE CHUBB FELLOW

On the screen, Yale Chubb Fellow appears. University chimes can be heard and the screen has a still photo of the Yale Chapel on campus.

Acheson walks on stage and speaks to audience.

Acheson

For some time, once Harry Truman left the White House, I was eager for him to come to Yale, my alma mater. I arranged for him to receive a Chubb Fellowship which meant that for several days he would be the honored guest of the university meeting with students and faculty.

This prospect delighted my former boss. He was deeply interested and very good with young people. And, as he told me, Yale was the kind of great university he wished he had been able to attend. Give the economic circumstances of his times, Truman had not been able to go to college and was largely self-taught. Word has it that he read just about every book in the Independence public library!

Acheson departs. Stage lights up revealing a typical Commons room (Yale banner or seal prominent) – with lots of books, well worn furniture, and several ‘old distinguished grad’ portraits on the walls.

Acheson and Truman enter to sound of applause from students. They sit down in comfortable chairs facing the audience. The Yale students who are ‘attending’ the session are in front of them, not seen, but their questions will be heard by voice overs (VO).

Scene begins with short intro by Acheson.

Acheson

Gentlemen of Yale, thank you for that hardy welcome.

It seems like just yesterday that I was sitting where you are now. It was here that I was exposed to many speakers who would inspire me, who gave us as undergraduates a sense of what our lives were worth and how to spend them for value, for a greater good. Our speaker today can speak to this higher calling better than anyone I know.

It is therefore my great privilege to present to you the 33rd President of the United States – and visiting Yale Chubb Fellow — Harry S Truman.

Applause heard from students.

Truman

Thank you, thank you all very much.

Let me begin by expressing my appreciation to Mr. Acheson for arranging this opportunity for me visit this esteemed institution and meet with you today.

I should add that for four years Mr. Acheson was my strong right arm as my secretary of state and I expect him to continue in that role in responding to your questions – warts and all!

Oh, one more thing. You have probably heard Secretary Acheson say that “the first requirement of a statesman is to be dull.” Well, I have found that he violates that dictum every time he speaks. And I hope I do today!

So, with that, let’s begin this interrogation. Who wants to start?

Student #1 (V/O)

Thank you for being here President Truman. We are honored to have you at Yale.

Truman acknowledges and smiles.

My question is simple, but it might be difficult to answer: What do you think makes a good president – what leadership qualities should he possess?

Truman

Actually, I think the answer to that is pretty straightforward.

My definition of the leader in a free country is a man – or, as of course will come in time, a woman – who can persuade people to do what they don’t want to do, or do what they’re too lazy to do, and like it!

Students laugh, as does Acheson who nods approvingly.

I’d also say that a man with thin skin has no business being president. Criticism is something a president gets every day, just like breakfast.

Now I’ll admit that I did not always react pleasantly to criticism — Truman smiles and Acheson nods – but I never did for a moment question the right of anyone to do so.

Student #1 continues

You just referred to a leader “in a free country.” Do you think this country could ever be a dictatorship?

Truman

The only way that could happen is if we got a liar in public office.

Student #2

Mr. President, I’d like to ask you about the Marshall Plan, how you got it through Congress, and why it wasn’t called the Truman plan since it was your initiative?

I’d also like to know why General Marshall gave the speech announcing it at Harvard and not here at Yale?

Students laugh.

Truman

(Also laughing) Well, I’m sure if Dean Acheson had been Secretary of State at that time, that speech would have been given right here!

Regarding the Marshall Plan, I believe it saved Europe. In all the history of the world, we are the first great nation to feed and support the conquered.

And we did this with strong bipartisan support – it passed the Congress by overwhelming majorities in both houses. That was the key.

Now, regarding its name. I was fully aware that anything sent up to the Republican Congress at that time with my name on it, they’d tear it apart — it would quiver a couple of times and die! So, I said, we’re going to call it the Marshall Plan, giving him the credit he deserved.

Students and Acheson laugh together.

Next question.

Student #3

Mr. President, you just mentioned the Republican Congress. If I remember correctly, you had a lot of fights with the Republicans – even calling them the ‘Do Nothing Congress’ when they were in charge. But you were still able to get some things done.

How did you do it?

Truman

Wasn’t easy, that’s for sure!

But it’s been my experience in public life that there are few problems that can’t be worked out if we make a real effort to understand the other fellow’s point of view, and if we try to find a solution on the basis of give-and-take, of fairness to both sides. It’s called compromise.

And that’s what I tried to do – and so did many Republicans members – (pauses) — who finally saw the light!

Student #4

Mr. President, could I ask you a somewhat personal question?

Truman

Go right ahead. If I want to stop you, you’ll know it.

Student #4 continues

You have referred to Mr. Acheson as your “strong right arm”. What was it about him that allowed you to work so well together? In many ways the two of you seem wholly dissimilar.

Truman

Well, you’re right, at least on one level.

I’m the son of a Midwest farmer; his dad was an Episcopal bishop in New England. I didn’t go to college; he went to Yale and Harvard law; early on I was a not-so-successful haberdasher in Kansas City while Dean was clerking for a Supreme Court Justice in Washington.

And, on top of all that, as you may have noticed, he’s a little taller than I am!

But I’ll tell you that these surface differences were far less important than the principles and values we shared – including a deep devotion to public service, loyalty, a sense of fairness, a distain for hypocrisy.

These things drew us together – and still do.

Next question.

Student #5

I was wondering if Secretary Acheson would answer that same question about you.

Acheson

Gladly.

Basic integrity. That’s the quality I most admire in President Truman. He is straightforward, decisive, simple and entirely honest. And through all his years in office he was free of the greatest vice in a leader – his ego never came between him and his job.

I would also say that, for those closest to him, Harry Truman was two men. One was the public figure – peppery, combative, the ‘give ‘em hell’ Harry.

Truman

(Interrupting) Dean, I never did give anybody hell. I just told the truth and they thought it was hell, especially the Republicans!

Laughter. Acheson resumes.

Acheson

And, as you may have heard, Mr. Truman once threatened — in a letter no less — to punch a Washington Post reporter in the nose for a bad review he wrote of his daughter Margaret’s opera recital.

Truman

(Interrupting again) He deserved it – still does!

Acheson

Smiles and resumes.

Now the other Harry Truman was kindly, modest, and courteous. He was always considerate of others’ feelings. He once told me what people don’t always think about is the power of a president to hurt. I never heard him say a harsh, bitter, or sarcastic word to anyone, whatever the offense or failure.

We used to have a saying in the White House – “a little touch of Harry” – to describe his good spirits when things weren’t going as planned. He would be the one to cheer us up.

One such “little touch” appeared in a motto framed on his desk in the Oval office – ‘The buck stops here.’ When things went wrong, he took the blame; when things went right, he gave his lieutenants the credit.

This was the “Mr. President’ we knew and loved. Next?

Student #6

Mr. Acheson, President Truman said at the beginning that this would be a “warts and all” session. Any “warts” in the Truman presidency that you would like to share with us?

Acheson

Now you are putting my skills as a diplomat to a true test!

Laughter.

But, actually, I do have one “wart” in mind.

He looks at Truman who says:

Truman

Please proceed Mr. Secretary. You have my full attention.

More laughter.

Acheson

Clearing his throat for dramatic effect, he proceeds.

Well, all presidents make mistakes, but the good ones learn from their mistakes and do not waste time obsessing about them.

That was certainly true of President Truman, he learned from all mistakes except one – the rapid answer in that nightmare of presidents, the press conference.

Acheson looks at Truman who is smiling. He continues.

With due respect, it is true that sometimes the president’s mind is not as quick as his tongue. He could often not wait for the end of a question before answering it. This tendency was a constant danger to him and a bugbear to his advisers.

Student #6 jumps back in

So was there anything you could do to correct this “tendency?”

Acheson

Yes, there was. We kept on hand, as a sort of first-aid kit, a handful of “clarifications” for the president’s press events.

Acheson pauses, then adds:

And if there was a slip up, we would console ourselves with the old proverb “To err is human.” We slightly revised it for our 33rd president — ‘To err is Truman’!

Laughter, with Truman joining in.

At this point, Acheson slowly stands up from his seat.

With that – and before any “clarifications” are needed – we need to bring this most enjoyable session with our Distinguished Chubb Fellow to a close.

Let me see if there are a couple of very brief questions. Yes, the student in the back.

Student #8

How does it feel to be an ex-President?

Truman

Well, I’ll tell you with a little story.

I recently went down to the Caruthersville Fair Grounds to give a speech, that’s in the southeast corner of Missouri. They had always been in my corner politically.

This time I wasn’t running for anything. I just went to show them I was interested in them, not just their votes.

Anyway, I had one of the biggest crowds they ever had.

They cheered as if I were still president.

So, I pretended I was still president and waved back!

Laughter and Truman adds:

Had a helluva good time. I think I’ll go back again next year and put up a stand and charge admission!

Final question.

Student #9

Thank you. It will be quick.

Recently I heard a television commentator say that you are likely to go down as one of our “greatest presidents.”

Do you agree with that assessment?

Truman

Pauses, then break into a grin.

Well, I wouldn’t say I was one of the great presidents, but I can tell you that I had a great time while I was trying to be one!

Laughter from students and big smile from Acheson.

Enthusiastic applause from students. Lights down.

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark.

Scene 7 “CAPTAIN WITH THE MIGHTY HEART”

On the screen, “Captain with the mighty heart” appears.

Unlike in earlier correspondence scene 2, spotlights are on both Acheson and Truman – they are sitting at their desks, in their respective studies — looking at each other as they read from their letters.

Acheson

Dear Boss:

I have just read in the paper of your mishap.

You have confirmed a nightmare fear of mine – the ever-lurking menace of the bathtub. Far more dangerous than the submarine or the bomb, nuclear or otherwise, it is a trap set for us old codgers. It is as dangerous to get into as to get out of, or to stay in.

Recently when we built a new bathroom onto our guesthouse at the farm, I refused to have any bathtub at all. Instead a gleaming white shower cabinet with a rubber floor. But still the wretched things lie in wait for us everywhere.

My heart goes out to you — battered, black-eyed, lung congested — all to pursue overrated cleanliness.

Yours ever, Dean

Truman

Dear Dean:

I did not fall in the bathtub, as was reported by the press. I was going into the bathroom, caught my heel on the sill which caused me to fall and hit my head against the washstand.

I wasn’t satisfied with the one fall, so I proceeded to hit the tub on the rebound and broke some ribs as well.

I am now getting along all right.

Sincerely yours, Harry

P.S. Yale still rings in my ears. I have never had a better time anywhere. It is what I have always wanted to do!

Acheson

Dear Mr. President,

Am very pleased that you are recovering nicely.

I will concede that the mishaps that await as I get older run counter to an idea that still hovers in my mind – that I am a promising lad and may get somewhere if I work hard and stay sober!

By the way, one of the glorious things that I have just read is a new edition of the correspondence between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. If you do not know it, by all means get it.

These were two robust old codgers!

Affectionately, Dean

Truman

Dear Dean,

I much appreciate your calling to my attention the Adams-Jefferson letters. As you know, history is my favorite subject.

For me, history is never just something in a book. It is part of life and of interest to me because it has to do with people. When I speak of Andrew Jackson or John Quincy Adams, or Abraham Lincoln, I feel like I am talking about someone I know.

What I find most interesting about the ‘long course of human events’ has been its elements of continuity, including above all, human nature, which has changed little if at all through time.

So that’s why I often say, “There is nothing new in the world except the history you do not know.” That’s why I continue to read history every chance I get.

I would also recommend this for American presidents. Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.

Most sincerely, Harry

P.S. I was once asked by a young man if I read myself to sleep at night. No, I said, I like to read myself awake. Suggest you do it too!

Acheson

Dear Mr. President,

I have another book for you. I am enclosing an advance copy of my memoir, “Present at the Creation: My Years in the State Department.”

In writing about those years, I came close to reliving them again with you and hope I have captured some of our spirit and purpose that made them such a wonderfully satisfying adventure.

Without even asking your permission, I dedicated the book to you. It reads:

TO HARRY S. TRUMAN

“THE CAPTAIN WITH THE MIGHTY HEART”

Mr. President, you inspired and supported almost everything described in this book. I hope you will find it a worthy account of what we tried to do together.

Faithfully, Dean

Truman

Dear Dean,

I deeply appreciate your dedicating your book to me. I recall with great pleasure and satisfaction the years we spent together shaping American foreign policy.

You had the clearest view of the leadership role America should play in the postwar world and created many of the intellectual concepts that would undergird my decisions.

The Marshall Plan, Bretton Woods, the Truman Doctrine, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization – all had your imprint. Indeed, there would not have been a NATO without you.

The world has been – and will be – a much safer one as a result of your efforts, for years to come.

For all this and more you have your Nation’s gratitude – and mine.

Sincerely and gratefully yours, Harry

Acheson

Dear Boss,

Our most affectionate greetings go to you with this birthday note. May you stay well and have many more of them.

As the years pass your stature grows more and more imposing, not merely as the comparisons furnished are smaller and smaller, but also because what you did stands out more and more.

All of us who had the honor of serving under you will never forget the satisfaction of that experience.

Devotedly and respectfully, Dean

Acheson concludes, putting his letter in his lap. Truman then begins reading his response.

Truman

Dear Dean,

I was greatly pleased by your kind and generous letter on my birthday.

As we count up the years, sometimes you wonder if the old man with the scythe isn’t after you. I’m trying to out run him!

I’ve had a grand and full life from beginning to now. Wish I could live another 50 years at least and have a hand in the greatest future any Republic ever contemplated.

Dean, I love your letters and you too. I cherish our times together – good and bad — and wish we could relive them all!

Most sincerely, Harry

SCENE ENDS. Stage dark.

EPILOGUE / UNION STATION 1953

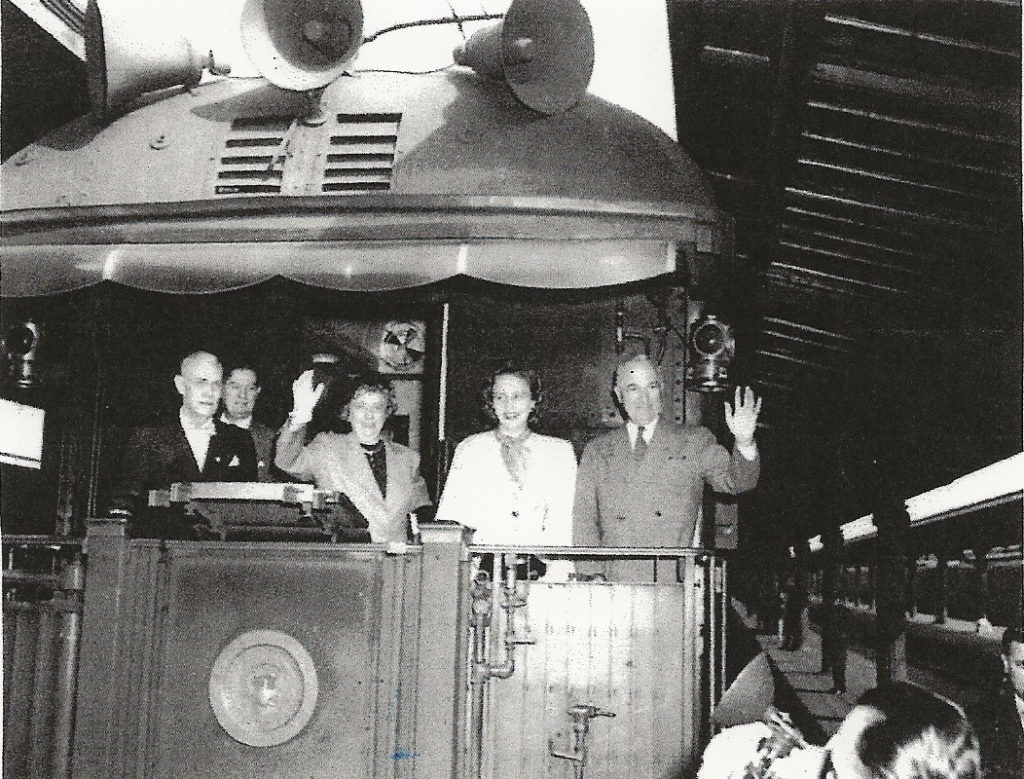

On the screen Union Station 1953 appears, followed by b & w film footage of the station packed with a vast crowd. The presidential car is at the end of the train for the late afternoon trip to Kansas City. Admonitory toots of the engine hasten those departing to get on board.

Sounds of people singing ‘For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow’ and ‘Auld Lang Syne.’

Footage freezes and spotlight focuses on Acheson, on the platform, looking at the scene. He turns to audience.

Acheson

What a sendoff for Harry Truman! How different from that day seven years ago when I stood here alone to welcome a disheartened president back to Washington. Today thousands showed up – old friends, Democratic senators, Supreme Court justices, members of the Cabinet, generals and ambassadors – all wanting the chance to shake the president’s hand and show their affection one more time before he departs.

Spotlight on Truman, standing on the rear platform of the train with Bess.

Truman

(Smiling broadly) Thank you! Thank you all! Mrs. Truman and I are on our way back to Independence where it all began for us.

We can’t adequately express our appreciation to you for this wonderful sendoff. I’ll never forget it if I live to be a hundred.

Truman pauses then with a big grin says:

And that’s just what I intend to do.

Crowd responds, many chanting “We want Harry!”

Voice from crowd: “What’s the first thing you plan to do when you get home?”

Truman

Glad you asked. I plan to carry the grips up to the attic. Then I’ll ask the Boss what else she has for me to do!

Bess

(Bess smiles and adds) That list is long!

Another voice from crowd – “Mr. Truman, you’re now an ex-President. What do you want to be called?”

Truman

I don’t care what people call me. I’ve been called just about everything you could imagine during my time in the White House.

But the fact is I’m now just plain Mr. Truman, private citizen. And that — I need not remind you ladies and gentlemen — is the highest honor this great Republic of ours can bestow.

Loud applause from crowd.

Valves underneath the train hiss. Conductor calls out “All aboard.”

Truman

Guess they want to keep on schedule! Hard to do that with politicians who love to talk!

Harry and Bess stand waving again, seeming reluctant for the moment to end. Then turn and enter the compartment.

More applause and cheers as the crowd bids farewell.

Footage of the train pulling out of station.

Acheson and Alice linger on platform as train departs. Alice turns to Dean.

Alice

He’s going back to Missouri.

Dean

And we’re going to miss him. He reminds people what a man in that office ought to be like. It’s character, just character.

He pauses, then adds:

And there goes the best friend in the world.

They wave a final goodbye, and walk away.

PLAY ENDS

Audience departs to the “Missouri Waltz,” made the official state song of Missouri in 1949 during Harry Truman’s presidency.

Bio Sketch of Karl Inderfurth

Karl Inderfurth is a former U.S. diplomat, serving as an assistant secretary of State and an ambassador to the United Nations in the Clinton administration. Earlier in his career he was an Emmy Award-winning ABC News national security and Moscow correspondent.

He co-authored Fateful Decisions: Inside the National Security Council (2004) and put his knowledge to good use when he played the role of the U.S. President in a well-received BBC Channel 4 docu-drama, ‘The Situation Room’.

His interest in the presidency has long drawn him to the years Harry Truman and Dean Acheson served in office and laid the foundation for America’s leadership role in the post-World War II world order.