This Day in History | July 26, 2022

The National Security Act of 1947 at 75 Years

By William Inboden, executive director of the Clements Center for National Security and associate professor of Public Policy and History at the LBJ School of Public Affairs

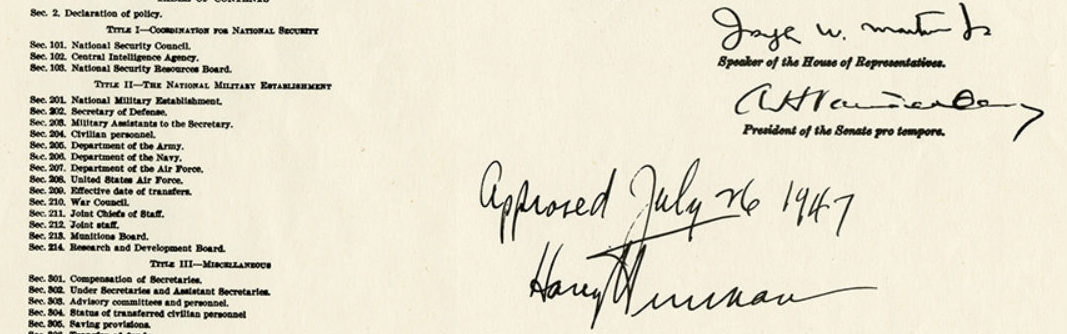

Seventy-five years ago, on July 26, 1947, President Harry S. Truman signed into law the National Security Act of 1947. The scholar Douglas Stuart has rightly called it “the law that transformed America.” Some of the most important institutions of America’s national defense and international leadership, including the National Security Council, Central Intelligence Agency, Department of Defense, and Air Force, all trace their birth to this one law.[1]

As the National Security Act of 1947 enjoys its 75th anniversary, it has in a way come full circle back to its founding purposes.

When President Truman signed it into law, one of his foremost concerns was organizing the United States government to resist Kremlin aggression. Three quarters of a century later, in 2022, President Biden and his administration find themselves wielding the main instruments of that same law in once again resisting Kremlin aggression, this time in supporting Ukraine’s resistance to the Russian invasion.

Virtually every aspect of America’s policy regarding the invasion derives from Truman’s National Security Act, including President Biden’s decisions at National Security Council meetings, the CIA’s early warnings about Russia’s intention to invade Ukraine, intelligence assistance to Ukrainian forces, the massive provision of weapons and ammunition to Ukraine led by the Pentagon, and the unprecedented economic sanctions imposed on Russia by the United States and our allies.

Soviet Influence and the Need to Act

When the Truman administration led the law’s negotiation and passage, World War II had ended less than two years earlier. Yet already Washington DC watched with growing alarm as Moscow – its former ally in the war – accelerated its efforts to extend the Soviet Union’s influence throughout Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

Just four months earlier in his landmark “Truman Doctrine” speech of March 12, 1947, the president had declared a new American policy “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.” The immediate goal was supporting the embattled governments of Turkey and Greece in their fights against Soviet-sponsored communist insurgencies. But the language and logic of the Truman Doctrine made clear that American opposition to communist expansion would extend across the globe, a policy that would continue for the next four decades of the Cold War.

President Truman delivers the “Truman Doctrine” speech to a joint session of Congress. Credit: International News Service

As he faced this unprecedented challenge from Soviet communism, Truman realized that his country was ill-equipped to meet it. World War II may have ended in an allied victory, but it had also revealed many deficiencies in the US government. Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor stemmed in part from poor intelligence collection, and inadequate communication and policy coordination between the Army, Navy, and State Department. America’s lack of a professional intelligence service had been only partly compensated by the improvised creation of the Office of Strategic Services, then disbanded at the end of the war. The unprecedented importance of air warfare was not matched by an Air Corps subordinate to the Army. And there existed no institution to coordinate and integrate all of the various military, intelligence, diplomatic, and economic policies involved in warfare – or to ensure that the president of the United States could wield executive authority over his own government even in peacetime.

National Security for a New Era

Truman was aware of the insufficiencies, but addressing them took on new urgency as he confronted the Soviet threat and the concomitant need for American leadership in a world still recovering from the ravages of war. Among its several provisions, the Act created the National Security Council (NSC), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the Air Force, and also unified the military services under what would become the Department of Defense.

The same day that he signed the bill into law, Truman nominated James Forrestal as his first Secretary of Defense. Acting with dispatch, the Senate voted to confirm Forrestal’s appointment later that night.

James Forrestal is sworn in as the nation’s first Secretary of Defense by Chief Justice Fred Vinson, while the top ranking civilian officials and military personnel witness the ceremony. Left to right are General Dwight D. Eisenhower, John L. Sullivan, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Senator Stuart Symington, Major General Alfred M. Gruenther and Thomas J. Hargrave. Credit: Harry S. Truman Library and Museum

Forrestal wrote to Truman of his gratitude that “we have a bill which, as you have expressed it, gives us the beginnings of a national military policy for the first time since 1798.”[2]

Though many challenges remained on implementation, and the legislation would need revision two years later to clarify and strengthen certain provisions, Truman’s point was correct. For most of American history the Army and Navy had been entirely distinct entities, with different policies and authorities, and little alignment in wartime beyond what presidents themselves had been able to provide. Now the commander-in-chief would have a Secretary of Defense leading a Department of Defense overseeing each military service. The Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines would be coordinated jointly under the umbrella of American national security policy.

While the law’s provisions concerning the Pentagon were rather detailed, as scholar Douglas Stuart observes “the sections of the [law] that established the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency fulfilled Napoleon’s guidelines for a good constitution – they were short and vague.”[3] Such brevity about the roles and responsibilities of the NSC and CIA could have been a liability, but Truman and his lieutenants soon turned it into an asset. In the next four years Truman would adapt and use the NSC to establish his Cold War strategy and navigate a cascade of crises including the Soviet blockade of West Berlin in 1948, the fall of China to communism and Soviet detonation of an atomic bomb in 1949, and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950. Similarly, he and his early Directors of Central Intelligence soon grew the CIA’s functions and mission to go beyond intelligence coordination to include the clandestine collection and analysis of intelligence, and the conduct of covert action programs.

Looking Ahead to the Next 75 Years

The Act has proven remarkably resilient over its 75 years. Its provisions sustained American foreign and defense policy through to the peaceful end of the Cold War, the changed global landscape of the 1990s, the September 11th era of terrorism and wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and now our present moment of great power competition with China and Russia.

As principles, it establishes the president’s authority over national security policy, makes clear that national security encompasses all elements of American power, affirms that intelligence is indispensable to foreign policy, and unifies the military services under the common cause of national defense. In flexibility, it gives each president considerable latitude in how to structure and employ its instruments, including the NSC, CIA, and Pentagon.

As the United States faces the unfolding national security landscape of the 21st century, from an aggressive China and Russia, belligerent Iran and North Korea, and resilient terrorist groups, to climate change, disease pandemics, cybersecurity, and the global erosion of democracy and human rights, there are persistent calls for creating new institutions and instruments to help tackle these challenges. This is correct; our present moment does need new policies and tools. Yet such efforts should take heart that three quarters of a century ago, in a previous era of geopolitical ferment, the United States showed that it could undertake an ambitious effort of institutional creation and renewal. And that any new endeavors can build on those venerable institutions from 1947 that today still serve our nation well.

William Inboden is executive director of the Clements Center for National Security and associate professor of Public Policy and History at the LBJ School of Public Affairs, both at the University of Texas at Austin. Prior to academia, he worked as a Congressional staff member and for the State Department and the National Security Council. He is the author of the forthcoming book The Peacemaker: Ronald Reagan, the Cold War, and the World on the Brink. In 2001, Dr. Inboden spent three weeks at the Truman Library conducting research for his dissertation (which later was published as Religion and American Foreign Policy, 1945–1960: The Soul of Containment). Of that experience, he writes, “It was a wonderful time, still one of my favorite research trips.”

[1] This paragraph adapted from William Inboden, “The National Security Act Turns 70,” War on the Rocks, July 26, 2017. [2] Walter Millis, ed. The Forrestal Diaries (New York: Viking Press 1951), 298-299. [3] Douglas Stuart, Creating the National Security State: A History of the Law that Transformed America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press 2008), 143.RELATED STORIES

CIA Director William J. Burns Accepts 2022 Harry S. Truman Legacy of Leadership Award