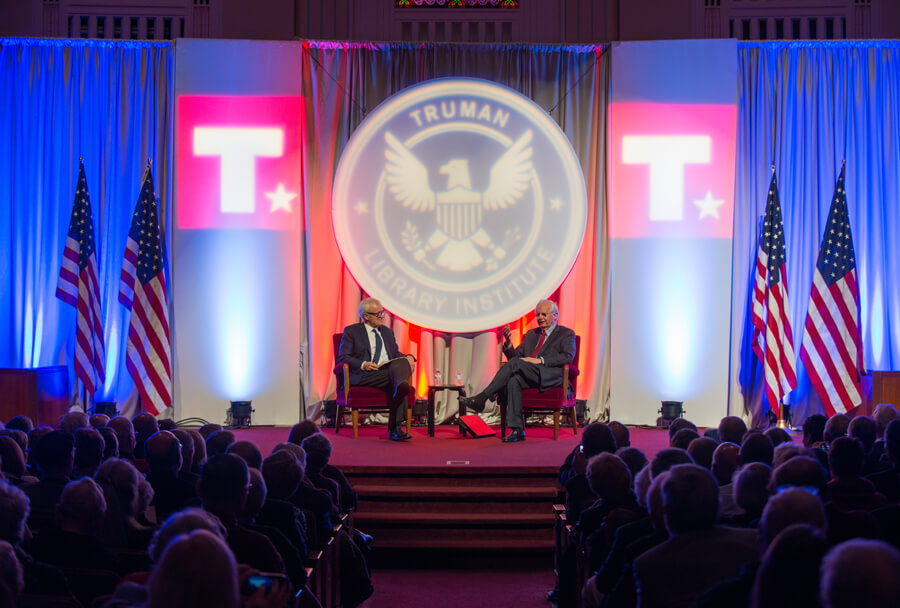

Event Highlights | November 25, 2014

Bill Moyers with Bob Kerrey

Earlier this month, Bill Moyers made an unprecedented encore appearance at the Truman Library Institute’s Howard and Virginia Bennett Forum on the Presidency to share his thoughts on the intertwined presidential legacies of Harry Truman and Lyndon Johnson. After making his formal remarks, Moyers sat down with former U.S. Senator for an informal, wide-ranging conversation about his life, liberal politics, and the state of the American presidency. Here are a few highlights from the November 1 event.

Bob Kerrey: I did not know that your legal name is Billy Don.

Bill Moyers: I was born in the South, and mothers loved to give their sons diminutive names like that.

Bob Kerrey: Billy Don. I like it.

Bill Moyers: I did too until I went to work at age 16 for the Marshall News Messenger and the managing editor, Spencer Jones, said, “Bill Moyers looks better in the byline.”

Bob Kerrey: [Laughter] So you, at age of 20, became an intern in Senator Johnson’s office.

Bill Moyers: It wasn’t called an intern then but in April of 1954 I was a journalism student and working full-time in journalism at college, and he was running for reelection in 1954. I had never met him, but I sat down one Saturday in April and wrote him a letter. “Dear Senator Johnson, I think I can help you in Texas, with young people.” The letter somehow got to his desk. He called the publisher of the newspaper in a little town in East Texas, where I’d gone to work at the age of 16, and asked how I was. The guy said, “He’s a good reporter. Give him a chance if you need somebody.” So he brought me up, and I worked in his correspondence section. He liked my letters. I had a run of good English teachers from sixth grade onto the 12th grade, and I did pretty well at letters. So there I was at age 20 writing letters to Dwight Eisenhower for him to sign, President Eisenhower, and all of that.

Bob Kerrey: Then you came back and were ordained a Baptist minister. You obviously have a skill at preaching. Was that a close call?

Bill Moyers: Lyndon Johnson said to me once that there are three ways for a poor boy to get ahead in Texas: politics, preaching or teaching. In the summer of ‘54, I had a kind of emotional crisis. I was in Washington. Joseph McCarthy was holding forth. I went to some of the hearings and was dismayed and depressed by what I saw. I said to my fiancée, “Judith, I think I’d rather go teach at Baylor University quite frankly.” I went to University of Denver and got a graduate degree in Theology, Church, and State Relations, then a Master of Divinity degree at Southwestern Theological Seminary.

Lyndon Johnson said to me once that there are three ways for a poor boy to get ahead in Texas: politics, preaching or teaching.

I was set to begin my PhD in American Civilization when Lyndon Johnson called and said, “I’m going to make a run here next year.” This is December of 1959. He’s going to make a try at the presidency at the nomination of the Democratic Party, and he was looking for a Boy Friday. “I want you at my side.”

So I went up. On the way to Washington Judith said, “What is he offering you?” “What do you mean?” I said. “I mean, what are you going to be making?” We had a six-month-old child, and we hoped to have another one, and I said, “I didn’t ask him.” She said, “He didn’t tell you?” I said, “I don’t think he does that sort of thing.” [Laughter] That’s the story. It’s a long story. Everybody’s story is complicated. One door opens, another closes.

Bob Kerrey: Talk a little bit about the difficulties of decision-making inside of that White House.

Bill Moyers: Well, be mindful that in 1964, ‘65 and ‘66 it was a wholly different time. We had 10 special assistants in the White House. We didn’t have a chief of staff. Johnson was his own chief of staff. He was the actual center of these folks, and we had easy access to him. I can’t imagine what it would be like today. In fact, I will say that in 1992 Bill Clinton asked me to join his White House staff, and two years later asked me to become his Chief of Staff. I didn’t want to do it, didn’t do it. Jimmy Carter had asked the same thing in 1978.

Bob Kerrey: You should have said yes to Carter. We’d have a different world today. Shame on you. [Laughter]

Bill Moyers: I wouldn’t know what to advise Barack Obama today, Bob, because this is an impossible job. Abraham Lincoln had two assistants. Johnson had 10. Now there are hundreds in the White House. There is no human being who can process the amount of information deliberately enough to reach a considered judgment in the United States today. It’s an out-of-date system in an out-of-control world. Whatever his own mistakes, there is more than Barack Obama can process in the course of a day, and you’ve seen him. He looks fatigued. His hair is white in just six years. It’s an impossible job. Our whole constitutional system needs restructuring. Somebody said to me tonight, I think it was you, that no modern CEO would organize his office the way the White House is organized. You couldn’t keep it going. That’s a real crisis. The crisis of the presidency is that there is no one who can do it.

The crisis of the presidency is that there is no one who can do it.

Bob Kerrey: Well, of course no modern CEO would allow the people to elect their board of directors, let alone 535 members of the board of directors. [Laughter]

Bill Moyers: Exactly.

Bob Kerrey: What happened to the liberal agenda that came out of the great society?

Bill Moyers: I just turned 80. I’ve lived long enough to see the slope behind me. For a long time I thought the liberal dispensation was the norm in this country. I thought the colonial period or the revolutionary period was a liberal dispensation. By that I mean enlarging the franchise – you enlarge the franchise of democracy so that more and more people can participate. But I have decided that this is a very conservative society. One third of the colonists fought the revolution, took part and supported the revolution. One third supported the Tories. One third stood on the sidelines waiting to see who would win so they could monetize the results. I think that’s essentially the United States. I’m beginning to think that the gains we made, in the progressive era, succeeded only because William McKinley was assassinated and Theodore Roosevelt succeeded. Accidental presidents have, more often, brought liberal activity than elected presidents. That may tell you something.

I have such awe and admiration for Harry Truman. There was no mandate, popular mandate for what he did for civil rights.

I have such awe and admiration for Harry Truman. There was no mandate, popular mandate for what he did for civil rights. No polls were in favor of the human rights campaign. There were no protests in the streets. No Selma, no march on Washington. He took [executive action] for two reasons: because he thought it was morally right, but also because he was a savvy politician, and he knew that the way the South would react to the measures he was proposing to take by executive order. He was the first president I think to see the potential of the African-American vote.

And here’s another thing I admire about Truman. Even though he admired the people around Roosevelt, he immediately began to replace them with his own people. Lyndon Johnson pleaded with the Kennedy staff and the Kennedy cabinet to stay on because he knew he needed them. I was closer to the Kennedy staff because of my role in the 1960 campaign, but you always need to bring your team in. Particularly in foreign policy, they were locked into the same gridlock of imagination that would ultimately bring us down and bring the nation down. It would have helped if it had some fresh thinking.

Bob Kerrey: Weren’t you attacked personally for dancing when you were in the White House?

Bill Moyers: A photographer for The Washington Post took that picture, and it was on the front page of over 200 pages the next morning. The conservatives seized on that to criticize us for having a good time while we were sending young men to Vietnam. You know what? That was fair criticism; it made me think that when you participate in ordering young men, now women, to lend their lives in a fight of no return, you should change your behavior. Today, we are in an endless war far more expensive than Vietnam, except in lives. We are in a war, whatever you want to call it. The best thing we could do today would be to require a year or two of national service for every young person of 18 and to ask for a war tax on the wealthy. [Applause]

Bob Kerrey: Here’s a question from the audience, “Why can’t we win the war on poverty?” Why is it so hard to get people to become more sympathetic to people who are working but still living in poverty? There was a lot of enthusiasm for Johnson’s “Great Society” and we had far less income inequality in 1964 than we do today.

Bill Moyers: Oh, yes. We’re at the greatest rate of inequality in the nation’s history, including the 1920’s, the Roaring Twenties and the Gilded Age. We didn’t really fight the war on poverty. We haven’t won the war on poverty because it’s intrinsic. It’s deep and it takes time. And we don’t get behind it. We don’t get behind it the way we get behind the Royals or the Jets or the Yankees.

We haven’t won the war on poverty because it’s intrinsic. It’s deep and it takes time. And we don’t get behind it. We don’t get behind it the way we get behind the Royals or the Jets or the Yankees.

Bob Kerrey: So what would you say if a 20-year-old asks you whether or not you would advise them to take a job in Washington as an intern or as a staff? Would you advise young people to go into politics?

Bill Moyers: I still do even though it’s changed so much. It’s a different city. It’s a different craft. It’s a different game. It’s so monetized today that I think it’s very hard for young people to find a relationship with the principal that I had with Lyndon Johnson. But still I cannot give up on politics because for the moment it still is – who said it? – “the steed that we ride to democracy?” Young people who feel they want to try to change our dysfunctional system should give it a try.