TRU History | August 6, 2021

Surplus WWII-Era Purple Hearts Still Being Awarded

A half-million medals are a reminder of the lives not lost in the Pacific Theater during World War II.

By D. M. Giangreco

Excerpted from “75 Years Later, Purple Hearts Made for An Invasion of Japan are Still Being Awarded,” originally published by George Washington University’s History News Network.

The Purple Heart is a military decoration which goes to troops wounded in battle and to the families of those killed in action. In 1945, the United States ramped up production in advance of the planned invasion of Japan.

An important thing to consider today, more than 75 years after the war’s end, is that when Harry S. Truman became president following Roosevelt’s death in April 1945, Americans from Walhalla, Texas, to Washington, DC, believed America to be in the middle of the war.

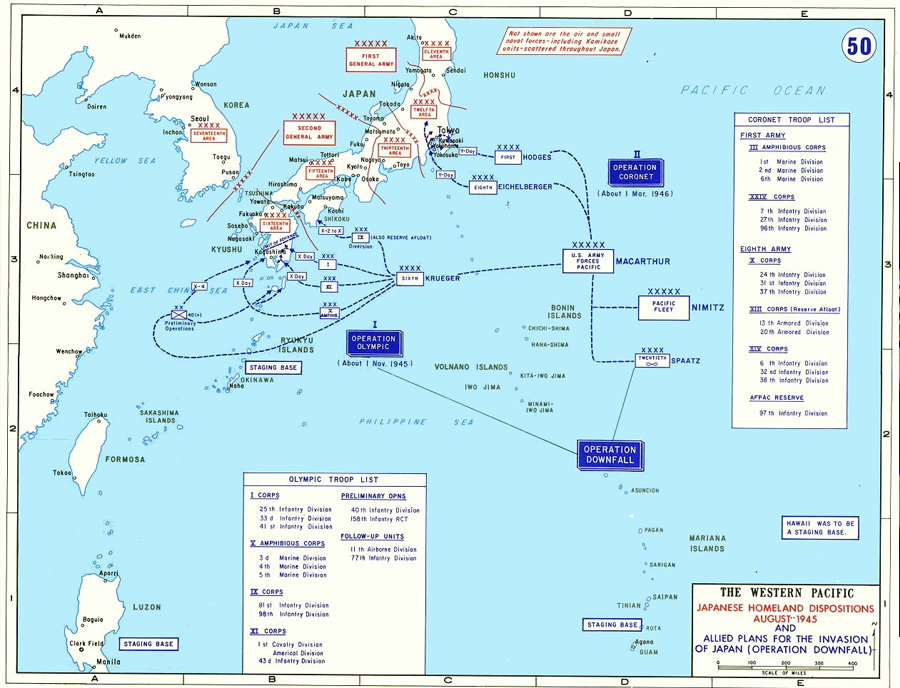

Nazi Germany had been defeated at a terrible cost, and now the final battles with Imperial Japan loomed. The initial invasion operation of Operation Downfall would be launched before Christmas 1945 against the southernmost main island of Japan with an even greater blow against the Tokyo area in the spring of 1946.

By July 1945, the US Army and Army Air Force had already suffered more than 945,000 all-causes casualties – mostly against the Nazis – and all wondered who would survive the Pacific fighting to sail home beneath “the Golden Gate in ‘48” after more years of brutal combat. As early as January 1945 the New York Times printed the dire warning of General George C Marshall and Admiral Ernest J. King that ‘’The Army must provide 600,000 replacements for overseas theaters before June 30, and, together with the Navy, will require a total of 900,000 inductions by June 30.’’

To meet these needs, the Army had organized a 100,000 men-per-month ‘’replacement stream’’ for the coming one-front war against Japan and the Army’s figures, of course, did not include Navy and Marine casualties.

Meanwhile, some War Department estimates indicated that the number of Japanese dead could reach between five to 10 million, with the possibility of 1.7 million to as many as four million American killed, wounded, and missing to combat, disease, and accidents if the worst case scenarios based on the recent Iwo Jima and Okinawa battles came true. Across the Pacific, the ultimate casualty figure being circulated within imperial circles in Tokyo was 20 million – a fifth of Japan’s population.

Fortunately, the invasion never took place. All the other implements of that war – tanks and LSTs, bullets and K-rations – have long since been sold, scrapped or used up, but the Purple Heart medals struck for their great grandfathers’ generation are still being pinned on the chests of young soldiers.

In all, approximately 1,531,000 Purple Hearts were produced for the war effort, with production reaching its peak as the Armed Services geared up for the invasion of Japan. Despite wastage, pilfering, and items that were simply lost, the reserve of decorations stood at approximately 495,000 after the war.

As Jim Pattillo, former president of the 20th Air Force Association stated, “Detailed information on the kind of casualties expected would have been a big help in demonstrating to modern Americans that those were very different times.”

Medical and training information in “arcanely worded military documents can be confusing,” said Pattillo, “but everyone understands a half-million Purple Hearts.”

Equally poignant was the reflection that came from a Vietnam vet – with a grandson and nephew in the Army today – who learned for the first time that he had received a medal minted for the fathers of him and his buddies.

“I will never look at my Purple Heart the same way again,” he said.

August 7 Is National #PurpleHeartDay.

Join our email list to receive Truman updates right in your inbox:

D. M. Giangreco is the author of 13 books including Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945-1947 (Naval Institute Press, 2019). His Journal of Military History article “Casualty Projections for the U.S. Invasions of Japan: Planning and Policy Implications” was awarded the Society for Military History’s Moncado Prize.