Book Excerpt: The Watchdog | April 24, 2024

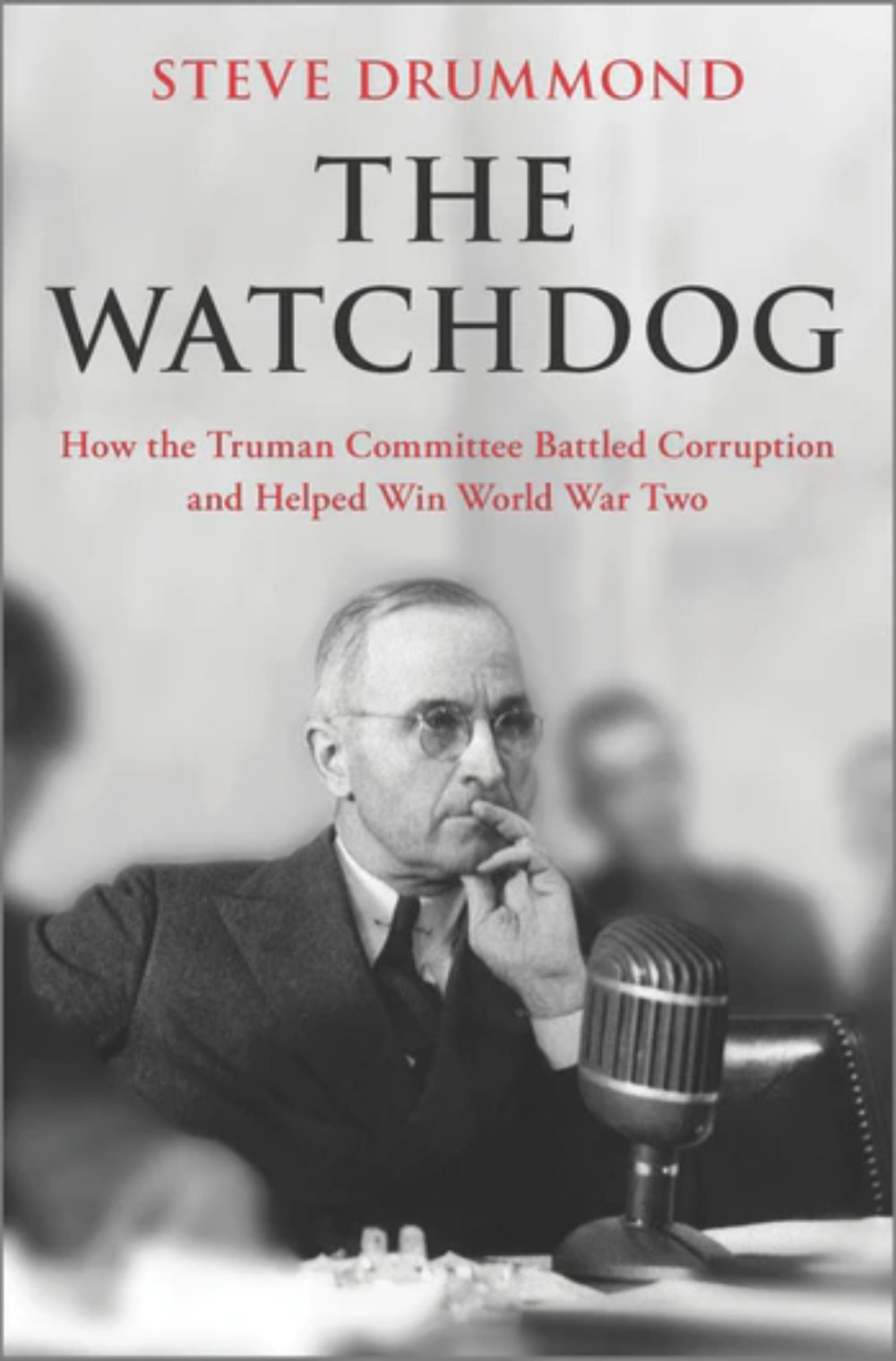

The Watchdog

How the Truman Committee Battled Corruption and Helped Win World War Two

By Steve Drummond

Winner of the 2024 Harry S. Truman Book Award

EXCERPT FROM THE WATCHDOG

Portland, Oregon, January 16, 1943

SATURDAY NIGHT WAS QUIETER THAN USUAL in war-booming Portland. A cold snap on Friday had killed two people in a storm that brought high winds and left a thin blanket of snow across the city. Temperatures were expected to sink into the low twenties.

At the Swan Island Shipyard in the northern part of the city, the brand-new tanker ship SS Schenectady floated gently in calm water, tied up at the fitting-out pier. The 16,500-ton vessel was a source of pride and wonder for the new shipyard, and for the whole city. At 523 feet long and 68 feet wide, it was the largest cargo ship ever built on the Pacific Coast, and the first of 147 tankers that would head down the Willamette River and off to war.

Fully loaded, the ship could carry six million gallons of fuel, and by prewar standards it had been built in no time. The keel was laid on July 1, and the hull launched on October 24. Twenty thousand workers watched that day as it slid down the rails and into the river, “her bow still dripping champagne.” Schenectady was declared finished on New Year’s Eve—two and a half months ahead of schedule. The ship, and the shipyard that built it, were just two examples of the miracles of war production taking place across the United States, achievements that would soon help turn the tide on battlefields around the world.

Outside Detroit, Henry Ford had built a giant airplane factory with an assembly line a mile long. The plant would eventually produce thousands of massive four-engine bombers; at its peak, a finished B-24 Liberator rolled off the line at the incredible rate of one every sixty-three minutes. Liberty ships—the cargo vessels that along with fuel tankers like the Schenectady would move the guns and food and planes and millions of tons of equipment across the oceans to the front lines—were being produced in ever greater numbers in shorter amounts of time. Driven by the innovations of shipbuilder Henry J. Kaiser, the first of them took 230 days to build; eventually the average would drop to just over a month.

To build these cargo ships and tankers, new shipyards were needed, and they began appearing in coastal cities seemingly overnight: Seattle, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Jacksonville. In little more than a year, Kaiser had transformed Swan Island, once home to Portland’s municipal airport, into a sprawling construction operation with thousands of men and women working shifts around the clock.

One big challenge was getting all those workers to and from their jobs, and finding housing for them when they weren’t working. The first dormitories at the shipyard had opened in November, and nine hundred workers moved into what would eventually be enough space for five thousand. A new ferry system was nearly completed that would shuttle workers to and from the yards.

The Schenectady was the first ship laid down at the new facility, and it was a new kind of ship—instead of being riveted together, the thick steel plates of these oil tankers (as with the cargo- carrying Liberty ships) were welded—a process that was faster, was less expensive and needed fewer highly skilled workers.

These new techniques were paying off—the Schenectady in late December had finished its sea trials and was declared fit for duty. On January 10 the shipyard had turned it over to the US Maritime Commission, and at 3:30 p.m. on the 16th, the ship’s new captain, V.P. Marshall, had officially taken charge. He was not on board that evening, though about thirty crewmen were as the ship was being loaded and prepared for her first voyage.

The sound, when it came, at 10:25 p.m., was heard as far as a mile away. Guards at the shipyard felt the ground shake. It sounded like an explosion and, this being wartime, the initial thoughts were of sabotage. An emergency radio call went out that a ship had blown up, and firefighters and police sped to the scene.

What they saw when they got there was the Schenectady, split almost completely down the middle. A ten-foot-wide crack ran across the deck and down the port and starboard sides just be-hind the deckhouse, as if giant hands had picked up the ship and snapped it in two. The keel had fractured through the bottom plates, but did not break, as the center of the ship jackknifed up out of the water. A faded photo shows Schenectady’s bow and stern settled to the bottom, the center portion up above the waterline with the dark, jagged fissure reflected in the water below.

Though it happened late, The Sunday Oregonian got the news onto the front page the next day, with a banner headline above the masthead: “New Tanker Breaks Apart, Sinks At Swan Is-land Dock.” No one was injured, the paper said, though later it would emerge that a seaman had broken his ankle in the rush to get off the ship.

By Monday, a few new details emerged, though already a veil of secrecy had dropped over the investigation. Armed coast guardsmen had sealed off the dock, FBI agents had begun interviewing the crewmen who were aboard, and everyone had been told to keep their mouths shut. Already though, an explosion had been ruled out, reported The Oregonian: definitely not, said the manager of the shipyard—if so, the edges of the giant crack would have blown outward.

But then, if not an explosion, what? There was some speculation initially that a hogback of sand or gravel on the river bottom had built up and forced the ship to split apart. But that was soon ruled out, too. With little new information coming in the following days, the story moved to the inside pages. On Tuesday came news that the FBI, having ruled out sabotage, had withdrawn, and the paper noted dutifully that morale among the shipyard’s employees, now back to work on the many other ships under construction, had not suffered.

Gradually—incredibly—it became clear that this brand-new, $3 million, 523-foot-long steel ship, cleared for sea duty and resting at its mooring in calm waters, had simply, mysteriously, broken in two.

Solving that mystery carried an urgency and importance far greater than a sailor’s broken ankle or the damage to this single ship. Because the Liberty ships and tankers like Schenectady were a vital element of Allied strategy in one of the most desperate and deadly fronts of the war. With Adolf Hitler in control of much of Europe, Great Britain and the Soviet Union depended for their survival on supplies that came by ship from across the Atlantic. And by early 1943, those ships also carried to Britain the troops, weapons, food and supplies that would, eventually, build up armies large and strong enough for the invasion of Europe. Challenging this massive supply effort were the German U-boats—the deadly submarines that throughout the war sent thousands of ships to the bottom of the Atlantic and prevented millions of tons of those goods from reaching their destinations. Both sides were in a race: the Allies to build more merchant ships and develop weapons and strategies to protect them from attack, the Germans to evade those defenses and sink more ships than the Allies could build. The stakes were deadly—during the war, the Battle of the Atlantic claimed more than one hundred thousand lives.

If the Liberty ships and tankers were flawed—if something was wrong with the design or the materials or the new techniques being used to build and launch them in numbers that before the war would have seemed impossible—the ramifications for the battle and for the outcome of the war were huge. Within days of the Schenectady’s breakup, a full investigation was underway, and Rear Admiral Howard Vickery, vice chairman of the US Maritime Commission, had arrived in Portland to take charge. But it would be weeks before the mystery was solved, and the answers would come not from the shipyard in Oregon, but from a congressional hearing room thousands of miles away in Washington, DC, and from a man in Pennsylvania who wrote a letter…

Critical Acclaim for The Watchdog

“This is an original and insightful chronicle of an overlooked yet critical stage in the career of Harry Truman. Not only did his path to the White House begin during World War II, his dogged devotion to detail and bipartisan passion saved many battlefield lives along with billions of dollars. Vividly, The Watchdog takes Truman from junior Missouri senator to his stunning ascension as leader of a world still fighting for freedom.”—Tom Clavin, New York Times bestselling author of Lightning Down: A World War II Story of Survival

“Steve Drummond has written an engaging, clear-eyed story of an important but overlooked chapter in the life of Harry Truman. The Watchdog will make you long for an era when government could be made to work.”—Evan Thomas, New York Times bestselling author of First: Sandra Day O’Connor

“It takes a thoughtful and agile reporter to see the story that others have overlooked. It takes an astute student of history to understand how the past speaks to the present. Steve Drummond is both. His unlikely tale of the Truman Committee, a shocking example of governmental success, will have readers looking anew at its chairman and namesake: the wonky senator from Missouri, with a distaste for partisanship and publicity, who became our thirty-third president.”—Robin Givhan, senior critic at large of The Washington Post and author of The Battle of Versailles: The Night American Fashion Stumbled into the Spotlight and Made History

“Drummond shines a light on a dark, forgotten corner of wartime history.”—Kirkus

“Drummond used a trove of documents to create this excellent narrative. The result is a well-written, engaging analysis of an often-overlooked and instructive aspect of Truman’s career that was essential to the war effort.”—Booklist

“Few people know the details of what [Harry Truman] did to make himself one of the most famous people in the nation, a story that is as fascinating as it is little-known, and which is told brilliantly in an important new book, The Watchdog. This is, indeed, a book that’s not only hard to put down, but which has a lot to say about how government can, and should work.”—Lessenberry Ink

Winner of the 2024 Harry S. Truman Book Award, The Watchdog is available wherever books are sold.

The Truman Library Institute will host Steve Drummond on September 18, 2024 for a public event and book signing in Kansas City, Missouri. Registration for the free public program will open August 1, 2024. For event alerts, sign up for TRU e-news here.

The Truman Library Institute will host Steve Drummond on September 18, 2024 for a public event and book signing in Kansas City, Missouri. Registration for the free public program will open August 1, 2024. For event alerts, sign up for TRU e-news here.

The Harry S. Truman Book Award is presented biennially and is generously endowed by Mary and John Hunkeler.